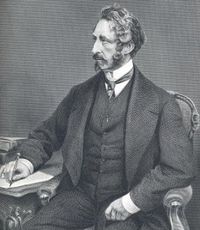

Edward Bulwer Lytton 1803 – 1873

July 16, 2008

Edward George Earle Lytton

Bulwer Lytton, 1st Baron

Lytton

1803 – 1873 was an English novelist, poet, playwright, and politician.

Edward George Earle Lytton

Bulwer Lytton, 1st Baron

Lytton

1803 – 1873 was an English novelist, poet, playwright, and politician.

Edward Bulwer Lytton was a patient of homeopaths Frederick Hervey Foster Quin and James Manby Gully, and his wife was also an advocate of homeopathy, giving homeopathic remedies to her own children and to her daughter Emily Lutyens’s children (Emily Lutyens married Edwin Landseer Lutyens),

Edward Bulwer Lytton’s brother William Henry Lytton Earle Bulwer 1st Baron Dalling and Bulwer was also a friend of Frederick Hervey Foster Quin (Baron Dalling was married to Georgiana Wellesley, the niece of Arthur Wellesley 1st Duke of Wellington),

Edward Bulwer Lytton was a friend of Count d’Orsay and the Countess of Blessington, and he attended Spiritualist meetings with Jacob Dixon, Thomas Henry Huxley, John Tyndall and James John Garth Wilkinson. Edward Bulwer Lytton was also a close friend of William Francis Cowper Temple 1st Baron Mount Temple (1811-1888).

Edward Bulwer Lytton knew homeopathic supporter William Cullen Bryant and an eager advocate and patron of homeopathy. Philip Wynter Wagstaff was the physician of John Ruskin’s friend William Cowper Temple and his wife Mrs. Wagstaff was the homeopath of Edward Robert Lytton Bulwer Lytton, the son of Edward Bulwer Lytton.

Edward Bulwer Lytton was a patient of Frederick Hervey Foster Quin and James Manby Gully. He ’disliked and distrusted’ the medical profession, which he thought limited in outlook. He would visit alternative practitioners and homeopaths with his friend Harriet Martineau, and she laughed: ”How we must be hated by the medical profession, getting well without and in spite of them“.

In his sketch ’Better Never Than Late’ Edward Bulwer Lytton lampoons the lampooners of homeopathy, and he writes extensively about homeopathy in his “My Novel”, Or, Varieties in English Life. Nonetheless, In 1853, homeopath Charles W Luther wrote to Edward Bulwer Lytton to complaint about this satirical sketch. A Dr. Morgan was the homeopath in Edward Bulwer Lytton’s Rienzi: the last of the tribunes,

Edward Bulwer Lytton was a friend of Benjamin Disraeli and Archibald Philip Primrose 5th Earl Roseberry:

Primrose’s maternal grandfather was Philip Henry Stanhope 4th Earl Stanhope, who had been, with his close friend Edward Bulwer Lytton, a member of the occultic Orphic Circle in the 1830s.

Philip Henry Stanhope 4th Earl Stanhope was a secret agent, an amateur homeopath and a lifelong keen researcher into the occult…

Very close to Bulwer Lytton and Philip Henry Stanhope 4th Earl Stanhope in the 1830s and involved in their seances was the young dandy and aspiring politician Benjamin Disraeli, it was the aristocrat Bulwer Lytton who provided the socially unprivileged Benjamin Disraeli with his entree into “Society”.

Rudolf Steiner said that: Roseberry himself was not particularly important…” [but he was] “an individual who is backed by various concealed groups…the firm doctrine that had come into being in the secret brotherhoods must be heard resounding in the words of Roseberry, for we must learn to look in the right places…

Edward Bulwer Lytton was a member of several occult societies:

Many well-known individuals of the 19th cent. held membership in the Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia; John Yarker, Paschal Beverly Randolph, Arthur Edward Waite, Edward Bulwer Lytton, William Wynn Westcott, Eliphas Levi, Theodor Reuss, Frederick Hockley [1809-1885], William Carpenter [1797-1874], and many many more. The Societas Rosicruciana in Anglia was originally nothing but a study group, and did not work rituals.

Edward Bulwer Lytton wrote one of the very first science fiction novels called Vril: The Power of the Coming Race in 1870, which included a strange concept of a super healing energy which could be used for good or ill:

The novel centres on a young, independently wealthy traveler (the narrator), who accidentally finds his way into a subterranean world occupied by beings who seem to resemble angels, who call themselves Vril-ya. The hero soon discovers that they are descendants of an antediluvian civilisation who live in networks of subterranean caverns linked by tunnels.

There they live in their technologically supported Utopia, chief among their tools being the “all-permeating fluid” called ”Vril”, a latent source of energy which his spiritually elevated hosts are able to master through training of their will, to a degree which depends upon their hereditary constitution, giving them access to an extraordinary force that can be controlled at will.

The powers of the will include the ability to heal, change, and destroy beings and things—the destructive powers in particular are awesomely powerful, allowing a few young Vril-ya children to wipe out entire cities if necessary. The narrator suggests that in time, the Vril-ya will run out of habitable spaces underground and will start claiming the surface of the earth, destroying mankind in the process, if necessary.

The uses of Vril in the novel amongst the Vril-ya vary from an agent of destruction to a healing substance. According to Zee, the daughter of the narrator’s host, Vril can be changed into the mightiest agency over all types of matter, both animate and inanimate. It can destroy like lightning or replenish life, heal, or cure. It is used to rend ways through solid matter. Its light is said to be steadier, softer and healthier than that from any flammable material. It can also be used as a power source for animating mechanisms. Vril can be harnessed by use of the Vril staff or mental concentration.

A Vril staff is an object in the shape of a wand or a staff which is used as a channel for Vril. The narrator describes it as hollow with ‘stops’, ‘keys’, or ‘springs’ in which Vril can be altered, modified or directed to either destroy or heal. The staff is about the size of a walking stick but can be lengthened or shortened according to the user’s preferences.

The appearance and function of the Vril staff differs according to gender, age, etc. Some staffs are more potent for destruction, others for healing. The staffs of children are said to be much simpler than those of sages; in those of wives and mothers the destructive part is removed while the healing aspects are emphasized.

The destructive force is so great that the fire lodged in the hollow of a rod directed by the hand of a child could cleave the strongest fortress or cleave its burning way from the van to the rear of an embattled host. It is also said that if army met army and both had command of the vril-force, both sides would be annihilated.

Interestingly, the Vril-ya also use Vril to take baths: It is their custom also, at stated but rare periods, perhaps four times a-year when in health, to use a bath charged with vril. They consider that this fluid, sparingly used, is a great sustainer of life; but used in excess, when in the normal state of health, rather tends to reaction and exhausted vitality. For nearly all their diseases, however, they resort to it as the chief assistant to nature in throwing off the complaint.

Lord Lytton’s father died when he was four years old, after which his mother moved to London. A delicate and neurotic, but precocious, child, he was sent to various boarding schools, where he was always discontented until a Mr Wallington at Baling encouraged him to publish, at the age of fifteen, an immature work, Ishmael and Other Poems.

In 1822 he entered Trinity College, Cambridge, but moved shortly afterwards to Trinity Hall, and in 1825 won the Chancellor’s Gold Medal for English verse. In the following year he took his B.A. degree and printed for private circulation a small volume of poems, Weeds and Wild Flowers.

He purchased a commission in the army, but sold it again without serving, and in August 1827 married, in opposition to his mother’s wishes, Rosina Doyle Wheeler. Upon their marriage, his mother withdrew his allowance, and he was forced to set to work seriously.

His writing and his efforts in the political arena took a toll upon his marriage to Rosina, and they were legally separated in 1836. Three years later, she published a novel called Cheveley, or the Man of Honour, in which Lord Lytton (then still surnamed Bulwer) was bitterly caricatured.

In June 1858, when her husband was standing as parliamentary candidate for Hertfordshire, she appeared at the hustings and indignantly denounced him. She was consequently placed under restraint as insane, but liberated a few weeks later. This was chronicled in her book A Blighted Life.

For years she continued her attacks upon her husband’s character; she would outlive him by nine years.

Lord Lytton was a member of the English Rosicrucian society, founded in 1867 by Robert Wentworth Little. Most of Lord Lytton’s writings—such as the 1842 book Zanoni—can only be understood in light of this influence.

Lord Lytton began his career as a follower of Jeremy Bentham. In 1831 he was elected member for St Ives in Cornwall, after which he was returned for Lincoln in 1832, and sat in Parliament for that city for nine years.

He spoke in favour of the Reform Bill, and took the leading part in securing the reduction, after vainly essaying the repeal, of the newspaper stamp duties.

His influence was perhaps most keenly felt when, on the Whigs’ dismissal from office in 1834, he issued a pamphlet entitled A Letter to a Late Cabinet Minister on the Crisis.

Lord Melbourne, then Prime Minister, offered him a lordship of the admiralty, which he declined as likely to interfere with his activity as an author.

In 1838, then at the height of his popularity, he was created a baronet, and on succeeding to the Knebworth Estate in 1843, he added Lytton to his surname, under the terms of his mother’s will.

In 1845, he left Parliament and spent some years in continental travel, reentering the political field in 1852; this time, having differed from the policy of Lord John Russell over the Corn Laws, he stood for Hertfordshire as a Conservative. Lord Lytton held that seat until 1866, when he was raised to the peerage as Baron Lytton.

In 1858 he entered Lord Derby’s government as Secretary of State for the Colonies, thus serving alongside his old friend Benjamin Disraeli. In the House of Lords he was comparatively inactive.

He took a proprietary interest in the development of the Crown Colony of British Columbia and wrote with great passion to the Royal Engineers upon assigning them their duties there. The former HBC Fort Dallas at Camchin, the confluence of the Thompson and Fraser Rivers, was renamed in his honour as Lytton, British Columbia.

Lord Lytton’s literary career began in 1820, with the publication of his first book of poems, and spanned much of the nineteenth century. He wrote in a variety of genres, including historical fiction, mystery, romance, the occult, and science fiction.

In 1828 he attracted general attention with Pelham, a humorous, intimate study of the dandyism of the age which kept gossips busy in identifying characters with public figures of the time. A highly melodramatic sub-plot is interwoven.

By 1833, he had reached the height of his popularity with Godolphin, followed by The Pilgrims of the Rhine (1834), The Last Days of Pompeii (1834), Rienzi (1835), and Harold: Last of the Saxon Kings (1848). The Last Days of Pompeii was inspired by the painting on the same subject by Russian painter Karl Briullov (Carlo Brullo) which Bulwer-Lytton saw in Milan.

He also wrote The Haunted and the Haunters (1857), also known as The House and the Brain, included by Isaac Asimov in his anthology Tales of the Occult. _Pelham_ had been partly inspired by Benjamin Disraeli’s first novel Vivian Grey. Lord Lytton was an admirer of Benjamin Disraeli’s father Isaac D’Israeli, himself a noted literary figure, and had corresponded with him.

Lord Lytton and D’Israeli began corresponding themselves in the late 1820s, and met for the first time in March of 1830, when D’Israeli dined at Lord Lytton’s house. Also present that evening were Charles Pelham Villiers and Alexander Cockburn…

He penned many other works, including The Coming Race (also reprinted as Vril: The Power of the Coming Race), which drew heavily on his interest in the occult and contributed to the birth of the science fiction genre… Unquestionably, its story of a subterranean race of men waiting to reclaim the surface is one of the first science fiction novels. His play, Money, was produced at Prince of Wales’s Theatre in 1872.

Edward Bulwer Lytton wrote Confessions of a Water Patient, in a Letter to W. Harrison Ainsworth.