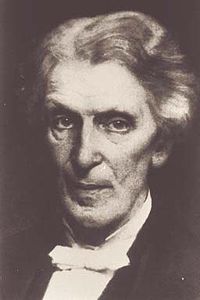

James Martineau 1805 - 1900

September 05, 2008

James

Martineau 1805 – 1900

was an English philosopher.

James

Martineau 1805 – 1900

was an English philosopher.

James Martineau was the younger brother of Harriet Martineau and a friend of Mary Augusta Ward and her father Tom Arnold, and brother of Matthew Arnold.

James Martineau was also a friend of George Croom Robertson, and a correspondent of William Cullen Bryant, and he was an ardent anti vivisection campaigner.

James Martineau was inspired by William Ellery Channing, Richard Whately Archbishop of Dublin, Frederick Denison Maurice, Herbert Spencer and Theodore Parker.

James Martineau wrote for the wrote for the _Westminster Review_ which was owned by John Chapman.

The _Westminster Review_ was founded in 1823 by Jeremy Bentham and James Mill as a quarterly journal for philosophical radicals, and was published from 1824 to 1914.

In 1851 the journal was acquired by John Chapman based at 142 the Strand, London, a publisher who originally had medical training.

The then unknown Mary Ann Evans, later better known by her pen name of George Eliot, had brought together his authors, including Francis William Newman, William Rathbone Greg, Harriet Martineau and the young journalist Herbert Spencer who had been working and living cheaply in the offices of The Economist opposite John Chapman’s house.

These authors met during that summer to give their support to this flagship of freethought and reform, joined by others including John Stuart Mill, William Benjamin Carpenter, Robert Chambers and George Jacob Holyoake. They were later joined by Thomas Henry Huxley, an ambitious young ship’s surgeon determined to become a naturalist.

Mary Ann Evans, who wrote under the name George Eliot, became assistant editor and produced a four page prospectus setting out their common beliefs in progress, ameliorating ills and rewards for talent, setting out a loosely defined evolutionism as “the fundamental principle” of what she and John Chapman called the “Law of Progress”.

From the writing of Mary Augusta Ward: For the New Brotherhood of Robert Elsmere had become in some sort a realized dream; so far as any dream can ever take to itself the practical garments of this puzzling world.

To show that the faith of Green and James Martineau and Stopford Brooke was a faith that would wear and work - to provide a home for the new learning of a New Reformation, and a practical outlet for its enthusiasm of humanity - were the chief aims in the minds of those of us who in 1890 founded the University Hall Settlement in London.

I look back now with emotion on that astonishing experiment. The scheme had taken shape in my mind during the summer of 1889, and in the following year I was able to persuade James Martineau, Stopford Brooke, my old friend Lord Carlisle, and a group of other religious Liberals, to take part in its realization.

We held a crowded meeting in London, and an adequate subscription list was raised without difficulty. University Hall in Gordon Square was taken as a residence for young men, and was very soon filled. Continuous teaching by the best men available, from all the churches, on the history and philosophy of religion, was one half the scheme; the other half busied itself with an attempt to bring about some real contact between brain and manual workers.

We took a little dingy hall in Marchmont Street, where the residents of the Hall started clubs and classes, Saturday mornings, for children and the like. The foundation of Toynbee Hall - the Universities Settlement - in East London, in memory of Arnold Toynbee, was then a fresh and striking fact in social history.

A spirit of fraternization was in the air, an ardent wish to break down the local and geographical barriers that separated rich from poor, East End from West End…

On the threshold also of the Settlement’s early history there stands the venerable figure of James Martineau - thinker and saint. For he was a member of the original Council, and his lectures on the Gospel of St. Luke, in the old “Elsmerian” hall, marked the best of what we tried to give in those first days.

I knew Harriet Martineau in my childhood at Fox How. Well I remember going to tea with that tremendous woman when I was eight years old; sitting through a silent meal, in much awe of her cap, her strong face, her ear-trumpet; and then being taken away to a neighboring room by a kind niece, that I might not disturb her further…

Between Harriet Martineau and her brother James, as many people will remember, there arose an unhappy difference in middle life which was never mended or healed. I never heard him speak of her. His standards were high and severe, for all the sensitive delicacy of his long, distinguished face and visionary eyes; and neither he nor she was of the stuff that allows kinship to supersede conscience. He published a somewhat vehement criticism of a book in which she was part author, and she never forgave it.

James Martineau was born in Norwich, the seventh child of Thomas Martineau and Elizabeth Rankin, the sixth, his senior by almost three years, being his sister Harriet Martineau. They were descended from Gaston Martineau, a Huguenot surgeon and refugee, who married Marie Pierre in 1693, and settled in Norwich.

His son and grandson, respectively the great-grandfather and grandfather of James Martineau, were surgeons in the same city, while his father was a manufacturer and merchant.

From http://www.martineausociety.co.uk/page3.html James Martineau was the seventh child and youngest son of Thomas, a textile merchant of Norwich Huguenot descent, and his wife Elizabeth Rankin, who came from Newcastle. He was thus kin of the Taylors, and through his mother to the Turners and Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell andher husband, and other northern Unitarian families.

Harriet Martineau, 3 years older than James, made him her special care and together they read the classics and anything else they could lay hands on, and sang a lot (mainly hymns). By the time James was 7, Rev Thomas Madge was minister at the Norwich Octagon; he ‘had been brought up C of E, but having become convinced of the truth of Unitarianism, and believing this alone to be the genuine gospel of Christ, he thought it his duty to proclaim it with greater distinctness than had hitherto been the practice at Norwich, thereby causing some secessions, and imparting to the congregation greater uniformity of theological colour’.

James himself recollected ‘some of my first awakenings of conscience and of spiritual faith came to me in the tones of that sweet voice’ - an influence which was confirmed when Mr Madge came to supper at the Martineaus every Sunday after evening service.

Young James was therefore in at the beginning of Norwich Unitarianism. At Harriet Martineau’s suggestion he was sent to Lant Carpenter’s famous school in Bristol and like her was very happy there. Both became lifelong friends of the Carpenters.

James, already well grounded in the classics, showed aptitude also for mathematics and physics as well as languages, and decided to become an engineer. He went to Derby as an apprentice and naturally lodged with the Unitarian minister, Rev E Higginson.

But the engineering was limited and instruction poor; James did not like the Higginsons but soon fell in love with the eldest daughter; and to get away from this difficult environment he spent as much time as possible with his Newcastle cousin Catherine Rankin and her husband, Henry Turner, now the young minister at Nottingham, who became his hero.

Henry soon became ill and died, and it was during his funeral sermon, by Rev Charles Wellbeloved, that ‘the scales fell from [James’s] eyes… the religious part of his life first commenced’ and he decided to train for the Unitarian ministry. His father agreed to forfeit the premium paid for his apprenticeship, and supply limited funds for his theological training.

Though unofficiallly engaged to Helen Higginson, there could be no question of marriage and her father forbad any contact between James and his beloved. Manchester College was then at York, and there James threw himself into his training and all the other student activities (including athletics).

His tutors included Wellbeloved, Turner and Kenrick; his fellow students Tagart, Higginson, Gaskell, Bache (to all of whom James was then or later connected by marriage) and Harriet Martineau’s fiance, and many other congenial spirits.

During vacations at home he was Harriet Martineau’s close confidant; he encouraged her first literary efforts and they went on a long tour of Scotland together in 1824, clouded by the death of their beloved eldest brother Thomas.

Within the next five years their father’s textile business failed, the father died and the family home was sold; from now on James needed to supplement his earnings as a preacher by teaching, both formally and with private pupils - luckily he was a born teacher.

His brilliance and industry as a student enabled him to obtain funding from the College to complete his course. Just in time, Lant Carpenter at Bristol needed a successor to head his school, and James eagerly accepted. He and Helen Higginson could now begin at least to discuss a ministry which would enable them to marry, and just in time again he was invited to Dublin, where Rev Philip Taylor needed an assistant.

In September 1828, still only 23, he sailed for Dublin, found a house in which he could take six pupils, started his ministry and in December went to Derby to be married and bring his bride back to their first home. A year later a daughter was born who died in infancy. Apart from this it was a happy time, but the congregation was small and James’s powers were underused. During this period he collected a first book of Hymns for Christian Worship.

After 3 years Dr Taylor died; James was to succeed him. But this meant taking as part of his stipend the Regium Donum or Royal Bounty, an ancient form of state benefit recognising the position of the Protestant church in a Catholic nation; this he felt unable to do. Moreover, since the money came to the congregation not the minister, he had to tell them so and give them the choice of forgoing the money and retaining him, or keeping the money and finding another minister. The letter he wrote them is a masterpiece, but the congregation took it as a resignation.

Principles apart, leaving Ireland involved the loss not only of the stipend but of the income from the school and the capital James and Helen had invested in the house; it was imperative that he should find another pulpit immediately. But some months, during which he attended his chapel as a member of the congregation, passed before he was invited as a candidate to Liverpool, and in the summer of 1832 the little family (son and daughter) took up residence.

He was a great success there, but he worked very hard: 7am young men’s class twice a week; 7 other classes 3 days a week 11-4.30 (3 quarters of an hour for dinner); 2 Sunday classes; writing Priestley papers and chemical lectures at Mechanics’ Institute; evening visits 2 or 3 times a week; Friday evenings preparation for Sunday: 10am lecture 11 service, then class for children; dinner 2.30; at 4 a class for senior girls, then boys; tea in the committee room; evening service 6.30.

After 4 years he started Tuesday evening discussion meetings, and once a month Thursday evening open house for young people. He also accepted the presidency of the Philosophical Society and took a full part in Liverpool’s social life; in his spare time he enjoyed teaching his own children languages, science and music. He did however take good holidays in Britain and abroad.

It was a prosperous period for the family - there were now four children, and 3 more arrived in Liverpool. Two clouds were looming, however: one was the declining health, and in 1846 the death, of a 10yr old son.

The other was the deteriorating relationship with Harriet Martineau, who had been pursuing her literary career and had achieved fame in political circles also on a two year tour of America, as well as in England, for her championship of anti-slavery, women’s rights etc. Setting out for Europe, she was taken ill and James had to go and bring her home.

During 4 years of self imposed seclusion, unceasing pain and constant writing at Tynemouth, near their eldest sister and her doctor husband in Newcastle (who pronounced her abdominal tumour incurable), a coolness sprang up. The first cause was Harriet Martineau’s attitude to correspondence; she had an obsession that all personal letters should be destroyed as soon as received: to keep them was a breach of confidence. James could not agree, regarding letters as keepsakes to be treasured. As a result, subsequent letters from Harriet Martineau became ‘short, summary and dictatorial… and betrayed a sharp impatience which gave notice that any exchange of ideas was useless and that the condition of happy intercourse must be the suppression of all serious dissent from her judgments.’

Then, in 1844 Harriet Martineau was persuaded to try Mesmerism as a cure, and to everyone’s surprise found it successful. She was soon able to travel again, set about building a house in Ambleside, writing voluminously on all topics.

Being Harriet Martineau, she had eventually to publish, in the form of Letters on the Law of Man’s Nature and Development not only her account of her cure, but her opinions, and those of her mesmerist, Henry George Atkinson, on Man, Nature and God, (they preferred a ‘First Cause’). Several members of the family were horrified, James among them. Unfortunately he felt obliged to write a scathing criticism of the book in a journal in which he was responsible for reviewing recent philosophical writing; and Harriet Martineau never spoke to him again.

In later life James clearly regretted his uncharacteristic hastiness, declaring his love for his sister unchanged, and tried to rationalise his reactions. One suspects that he was outraged less by Harriet Martineau’s desertion of the simple Christian piety which was their joint heritage than by the suspicion (which others had no scruples in assuming) that Harriet was in love with her curer who had supplanted him as hero in her eyes.

Meanwhile, James’s prowess as a lecturer had become famous. He was on the staff of the College, now returned to Manchester, which meant regular commuting between Manchester and Liverpool.

He took his now nearly grownup family to Germany for a year’s tour while a new chapel was being built at Hope St, Liverpool. It was opened on his return in Oct 1849, his old mentor Thos Madge preaching.

James was now at the height of his powers and his life inextricably involved with Unitarian affairs nationally - the Dissenters’ Chapels Act, the opening of the universities to dissenters without doctrinal tests, and the decision to remove Manchester College to London (associated with UCL) where in due course he became principal 1869-85, and president 1887.

James, though always calling himself a Unitarian, would never allow his congregation to be called so, insisting that they were individual thinkers agreeing only on the Universality of God. He hated controversy, above all about religion, regarding it as the antithesis of Christ’s teaching.

What could be more absurd than that, when proposed for the Chair of Philosophy at UCL in 1866, he was defeated by those who felt it “inconsistent with the [college’s] principle of complete religious neutrality… to appoint … a candidate eminent as a minister and preacher of one among the various sects which divide the religious world”.

James was always a devoted family man, and as soon as it could be afforded, took them all (including in due course two daughters in law and a son in law) on holiday together to Scotland, where a house near Aviemore became their annual base. From here they would meet him on return from his prodigious walks; in the evenings the Spinnies (as the 3 spinster daughters called themselves) would copy out his writings, and observe as he reached his 90s ‘how much more he notices outside things… the flowers, trees etc’ than when he had been immersed in his studies.

No grandchildren were born, but his genius for friendship bore fruit in the love of the many friends, young and old, who visited and maintained detailed and affectionate correspondence with him until his death at the age of 95 in January 1900.