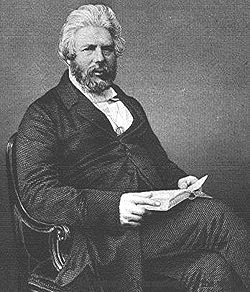

Robert Chambers 1802 – 1871

October 08, 2008

Robert

Chambers 1802 – 1871

was a Scottish author and publisher, who, in partnership with his

brother William

Chambers,

was highly influential in the middle years of the century. He was the

anonymous author of the Vestiges of the Natural History of

Creation.

Robert

Chambers 1802 – 1871

was a Scottish author and publisher, who, in partnership with his

brother William

Chambers,

was highly influential in the middle years of the century. He was the

anonymous author of the Vestiges of the Natural History of

Creation.

Robert Chambers was a friend of John Chapman and Spencer Timothy Hall, and a supporter of the Westminster Review. Robert Chambers was also a correspondent of Charles Darwin. Robert Chambers was also a friend of William Howitt and James John Garth Wilkinson (William Howitt, 4 Letters from William Howitt, 3 of Them to Robert Chambers, (1845). See also Swedenborg Archive K124 [a] Letter 6.5.1858 from Garth Wilkinson to Emma Anne Wilkinson).

Robert and his brother William reported on the homeopathic treatment of cholera in Edinburgh by John Rutherford Russell in their Edinburgh Journal in 1849, and again in 1852 when they reported on the controversy between allopathy and homeopathy and came out in favour of giving no drugs at all! (William Chambers, Robert Chambers, Chambers’s Edinburgh journal, (W. Orr, 1849). Page 133. See also William Chambers, Robert Chambers, Chambers’s Edinburgh journal, Volumes 17-18, (W. Orr, 1852). Page 175).

Robert and his older brother William Chambers were both born in the rural country town of Peebles in the Scottish Borders at the turn of the 19th century. In those days the town had changed little in hundreds of years. There was an old part of town and a new part of town, each consisting of little more than a single street. Peebles was mainly inhabited by weavers and labourers living in thatched cottages.

His father, James Chambers, made his living as a cotton manufacturer. Their slate roofed house was built by James Chambers’ father as a wedding gift for his son, and the ground floor functioned as the family workshop.

A small circulating library in the town, run by Alexander Elder, introduced Robert to books and developed his literary interests when he was young. Occasionally, his father would buy books for the family library, and one day Robert found a complete set of the fourth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica hidden away in a chest in the attic. He eagerly read this for many years.

Near the end of his life, Chambers remembered feeling “a profound thankfulness that such a convenient collection of human knowledge existed, and that here it was spread out like a well-plenished table before me”. William later recalled that for Robert, “the acquisition of knowledge was with him the highest of earthly enjoyments”.

Robert was sent to local schools and showed unusual literary taste and ability, though he found his schooling to be uninspiring and non-influential. His education was typical for the day. The country school, directed by James Gray, taught the boys reading, writing, and, for an additional charge, arithmetic. In grammar school it was the classics - Latin and Ancient Greek, with some English composition thrown in for good measure. Boys bullied one another and the teacher gave corporal punishment in the classroom for unruly behavior. Although uninspired by the school, Robert made up for this at the bookseller.

Both Robert and William were born with six fingers on each hand and six toes on each foot. Their parents attempted to correct this abnormality through operations, and while William’s was successful Robert was left partially lame. So while other boys roughed it outside, Robert was content to stay indoors and study his books.

Robert surpassed his older brother in his education, which he continued for several years beyond William’s. Robert had been destined for the ministry, but at the age of fifteen he dropped this intended career.

The arrival of the power loom suddenly threatened James Chambers’ cotton business, forcing him to close it down and become a draper. During this time, James began to socialize with a number of French prisoners of war on parole who were stationed in Peebles. Unfortunately, James Chambers lent these exiles a large amount of credit, and when they were abruptly transferred away he was forced to declare bankruptcy.

The family moved to Edinburgh in 1813. Robert continued his education, and William became a bookseller’s apprentice. In 1818 Robert, just 16 years old, began his own business as a bookstall keeper on Leith Walk. At first, his entire stock consisted of a some old books belonging to his father, amounting to thirteen feet of shelf space and worth no more than a few pounds. By the end of the first year the value of his stock went up to twelve pounds, and modest success came gradually.

While Robert built up a business his brother William expanded his own by purchasing a homemade printing press and publishing pamphlets as well as creating his own type. Soon afterwards, Robert and William decided to join forces - with Robert writing and William printing. Their first joint venture was a magazine series called The Kaleidoscope, or Edinburgh Literary Amusement, sold for threepence. This was issued every two weeks between 6 October 1821 and 12 January 1822.

It was followed by Illustrations of the Author of Waverley (1822), which offered sketches of individuals believed to have been the inspirations for some of the characters in Walter Scott’s works of fiction. The last book to be printed on William’s old press was the Traditions of Edinburgh (1824), derived from Robert’s enthusiastic interest in the history and antiquities of Edinburgh. He followed this with Walks in Edinburgh (1825), and these books gained him the approval and personal friendship of Walter Scott.

After Walter Scott’s death, Robert paid tribute to him by writing a Life of Sir Walter Scott (1832). Robert also wrote a History of the Rebellions in Scotland from 1638 to 1745 (1828) and numerous other works on Scotland and Scottish traditions.

On December 7, 1829, Robert married Anne Kirkwood, the only child of John Kirkwood.Together they had a total of 14 children, three of which died in infancy. Excluding these three, their children were Robert, Nina, Mary (Mrs. Edwards), Anne (Mrs. Dowie, mother of Ménie Muriel Dowie), Janet (Mrs. Frederick Augustus Lehmann), Eliza (Mrs. Priestly), Amelia (Mrs. Rudolf Lehmann), James, William, Phoebe (Mrs. Zeigler), and Alice.

The two brothers eventually united as partners in the publishing firm of W. & R. Chambers. In the beginning of 1832 William Chambers started a weekly publication under the title of Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal (known since 1854 as Chambers’s Journal of Literature, Science and Arts), which speedily attained a large circulation.

Robert was at first only a contributor. After fourteen numbers had appeared, however, he was associated with his brother as joint editor, and his collaboration contributed more perhaps than anything else to the success of the Chambers’s Edinburgh Journal.

Among the other numerous works of which Robert was in whole or in part the author, the Biographical Dictionary of Eminent Scotsmen (4 vols., Glasgow, 1832–1835), the Cyclopædia of English Literature (1844), the Life and Works of Robert Burns (4 vols., 1851), Ancient Sea Margins (1848), the Domestic Annals of Scotland (1859–1861) and the Book of Days (2 vols., 1862–1864) were the most important.

Chambers’s Encyclopaedia (1859–1868), with Andrew Findlater as editor, was carried out under the superintendence of the brothers. The Cyclopædia of English Literature contains a series of admirably selected extracts from the best authors of every period, “set in a biographical and critical history of the literature itself.” For the Life of Burns he made diligent and laborious original investigations, gathering many hitherto unrecorded facts from the poet’s sister, Mrs Begg, to whose benefit the whole profits of the work were generously devoted.

During the 1830s, Robert Chambers took a particularly keen interest in the then rapidly expanding field of geology, and he was elected a fellow of the Geological Society of London in

- Prior to this, he was elected a member of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1840, which connected him through correspondence to numerous scientific men. William later recalls that “His mind had become occupied with speculative theories which brought him into communication with Charles Bell, George Combe, his brother Andrew Combe, Neil Arnott, Edward Forbes, Samuel Brown, and other thinkers on physiology and mental philosophy”.

In 1848 he published his first geological book on Ancient Sea Margins. Later, he toured Scandinavia and Canada for the purpose of geological exploration. The results of his travels were published in Tracings of the North of Europe (1851) and Tracings in Iceland and the Faroe Islands (1856). However, his most popular book, influenced by his geological studies and interest in speculative theories, was a work to which he never officially attached his name.

The first edition of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation was released in 1844 and published anonymously. Literary anonymity was not uncommon at the time, especially in periodical journalism. However, in the science genre, anonymity was especially rare, due to the fact that science writers typically wanted to take credit for their work in order to claim priority for their findings.

The reason for Chambers’ anonymity was clear enough as soon as one began reading the text. The book was arguing for an evolutionary view of life in the same spirit as the late Frenchman Jean Baptiste Lamarck. Jean Baptiste Lamarck had long been discredited among intellectuals by this time and evolutionary (or development) theories were exceedingly unpopular, except among the political radicals, materialists, and atheists.

Chambers, however, tried to explicitly distance his own theory from that of Jean Baptiste Lamarck’s by denying Jean Baptiste Lamarck’s evolutionary mechanism any plausibility.

“Now it is possible that wants and the exercise of faculties have entered in some manner into the production of the phenomena which we have been considering; but certainly not in the way suggested by Jean Baptiste Lamarck, whose whole notion is obviously so inadequate to account for the rise of the organic kingdoms, that we only can place it with pity among the follies of the wise”.

Additionally, his work was far more sweeping in scope than any of his predecessors.

“The book, as far as I am aware,” he writes in his concluding chapter, “is the first attempt to connect the natural sciences in a history of creation”.

Robert Chambers was certainly aware of the storm that would probably be raised at the time by his treatment of the subject, and most importantly, he did not wish to get he and his brother’s publishing firm involved in any kind of scandal that could potentially ruin or severely impact their business venture. The arrangements for publication, therefore, were made through a friend named Alexander Ireland, of Manchester. To further prevent the possibility of any unwanted revelations, Chambers only disclosed the secret to four people: his wife, his brother William, Ireland, and George Combe’s nephew, Robert Cox.

All correspondence to and from Chambers passed through Alexander Ireland’s hands first, and all letters and manuscripts were dutifully transcribed in Mrs. Chamber’s hand to prevent the possibility of anyone recognizing Robert’s handwriting.

By implying that God might not actively sustain the natural and social hierarchies, the book threatened the social order and could provide ammunition to Chartists and revolutionaries. Anglican clergymen/naturalists attacked the book, with the geologist Adam Sedgwick predicting “ruin and confusion in such a creed” which if taken up by the working classes “will undermine the whole moral and social fabric” bringing “discord and deadly mischief in its train”.

The book was liked by many Quakers and Unitarians. The Unitarian physiologist William Benjamin Carpenter called it “a very beautiful and a very interesting book”, and helped Chambers with correcting later editions.

Critics thanked God that the author began “in ignorance and presumption”, for the revised versions “would have been much more dangerous”. Nevertheless, the book was undoubtedly a sensation and quickly went through a number of new editions. Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation brought widespread discussion of evolution out of the streets and gutter presses and into the drawing rooms of respectable men and women.

Chambers gave a talk on ancient beaches at the British Association for the Advancement of Science meeting at Oxford in May 1847. An observer named Andrew Crombie Ramsay at the meeting reported that Chambers “pushed his conclusions to a most unwarrantable length and got roughly handled on account of it by Buckland, De la Beche, Sedgwick, Roderick Murchison, and Charles Lyell. The last told me afterwards that he did so purposely that [Chambers] might see that reasonings in the style of the author of the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation would not be tolerated among scientific men”.

On the Sunday Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford, used his sermon at St. Mary’s Church on “the wrong way of doing science” to deliver a stinging attack obviously aimed at Chambers. The church “crowded to suffocation” with geologists, astronomers and zoologists heard jibes about the “half-learned” seduced by the “foul temptation” of speculation looking for a self-sustaining universe in a “mocking spirit of unbelief”, showing a failure to understand the “modes of the Creator’s acting” or to meet the responsibilities of a gentleman. Chambers denounced this as an attempt to stifle progressive opinion, but others thought he must have gone home “with the feeling of a martyr”.

Near the close of autumn, 1848, Chambers allowed himself to be brought forward as a candidate for the administrative position of Lord Provost of Edinburgh. The timing was especially poor, with others seeking any means possible to try and discredit his character. His adversaries found the perfect opportunity to do so in the swirling allegations that he was the author of the much reviled Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation.

William Chambers, in his Memoir of Robert Chambers, still sworn to secrecy despite his brother’s recent passing, makes his only mention of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation in connection with this affair: “(Robert) might have been well assured that a rumor to the effect that he was the author of ’Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation,’ would be used to his disadvantage, and that anything he might say on the subject would be unavailing.” Robert withdrew his candidacy in disgust.

In 1851 Chambers was one of a group of writers who joined the publisher John Chapman in reinvigorating the Westminster Review as a flagship of free thought and reform, spreading the ideas of evolutionism.

The Book of Days was Chambers’s last major publication, and perhaps his most elaborate. It was a miscellany of popular antiquities in connection with the calendar, and it is supposed that his excessive labour in connexion with this book hastened his death.

Two years before, the University of St Andrews had conferred upon him the degree of doctor of laws, and he was elected a member of the Athenaeum Club in London. It is his highest claim to distinction that he did so much to give a healthy tone to the cheap popular literature which has become so important a factor in modern civilization.

Robert Chambers died on March 17, 1871, in St. Andrews. He was buried in the Cathedral burial ground in the interior of the old Church of St. Regulus, according to his wishes.

A year after Robert’s death, his brother William published a biography under the title Memoir of Robert Chambers; With Autobiographical Reminisces of William Chambers. However, the book did not reveal Robert’s authorship of the Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation…

Alexander Ireland, in 1884, issued a 12th edition of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation with Robert Chambers finally listed as the author and a preface giving an account of its authorship. Alexander Ireland felt that there was no longer any reason for concealing the secret.