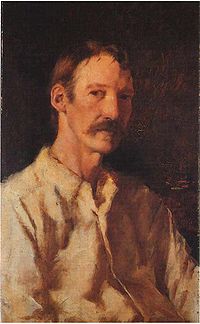

Robert Louis Balfour Stevenson 1850 –1894

January 02, 2009

Robert Louis Balfour

Stevenson 1850

–1894 was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer.

Robert Louis Balfour

Stevenson 1850

–1894 was a Scottish novelist, poet, essayist and travel writer.

Robert Louis Stevenson was a close friend of Henry James Jnr, George Meredith and Leslie Stephen, the husband of William Makepeace Thackeray, and a friend of numerous homeopaths and homeopathic supporters.

Stevenson was also a close friend of Rev. Walter Jekyll, the brother of Gertrude Jekyll, and he borrowed the family name for his famous novella Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

Robert Louis Stevenson was also a close friend of Edmund William Gosse, who was married to Ellen Nellie Epps (a close friend of Siegfried Sassoon’s mother), and whose whose brother Washington Epps was a famous homeopath. Ellen Nellie Epps was the daughter of homeopath George Napoleon Epps. John Epps, Ellen Nellie Epps’s uncle in law, was also a famous homeopath, and James Epps, another of Ellen Nellie Epps’s uncle in law’s, was a famous homeopathic chemist.

It was during this period he made most of his lasting friendships and met his future wife, Fanny Vandegrift Osbourne, an American who was 10 years his senior and married at the time.

Among his friends were Sidney Colvin, his biographer and literary agent; William Ernest Henley, a collaborator in dramatic composition; Mrs. Sitwell, who helped him through a religious crisis; and Andrew Lang, Edmund William Gosse, and Leslie Stephen, all writers and critics.

He also made the journeys described in An Inland Voyage and Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes. In addition, he wrote 20 or more articles and essays for various magazines. Although it seemed to his parents that he was wasting his time and being idle, in reality he was constantly studying to perfect his style of writing and broaden his knowledge of life, emerging as a man of letters.

Stevenson and Fanny Vandegrift Osbourne met at Grez in September 1876. Although Stevenson shortly afterwards returned to Britain, Fanny apparently remained in his thoughts, and he wrote an essay “On falling in love” for the Cornhill Magazine. They met again early in 1877 and became lovers. Stevenson spent much of the following years with her and her children in France.

Then, in August 1878, Fanny returned to her home in San Francisco, California. Stevenson at first remained in Europe, making the walking trip that would form the basis for Travels with a Donkey; but in August 1879, he set off to join her, against the advice of his friends and without notifying his parents.

He took second class passage on the Devonian, in part to save money, but also to learn how others travelled and to increase the adventure of the journey. From New York City he travelled overland by train to California. He later wrote about the experience in The Amateur Emigrant. Although it was good experience for his literature, it broke his health, and he was near death when he arrived in Monterey. He was nursed back to health by some ranchers there.

By December of 1879 he had recovered his health enough to continue to San Francisco, where for several months he struggled “all alone on forty five cents a day, and sometimes less, with quantities of hard work and many heavy thoughts,” in an effort to support himself through his writing, but by the end of the winter his health was broken again, and he found himself at death’s door.

Fanny Vandegrift Osbourne — now divorced and recovered from her own illness — came to Stevenson’s bedside and nursed him to recovery. “After a while,” he wrote, “my spirit got up again in a divine frenzy, and has since kicked and spurred my vile body forward with great emphasis and success.” When his father heard of his condition he cabled him money to help him through this period.

In May, 1880, Stevenson married Fanny although, as he said, he was “a mere complication of cough and bones, much fitter for an emblem of mortality than a bridegroom.” With his new wife and her son, Lloyd, he travelled north of San Francisco to Napa Valley, and spent a summer honeymoon at an abandoned mining camp on Mount Saint Helena. He wrote about this experience in The Silverado Squatters.

He met Charles Warren Stoddard, co-editor of the Overland Monthly and author of South Sea Idylls, who urged Stevenson to travel to the south Pacific, an idea which would return to him many years later.

In August 1880 he sailed with his family from New York back to Britain, and found his parents and his friend Sidney Colvin on the wharf at Liverpool, happy to see him return home. Gradually his new wife was able to patch up differences between father and son and make herself a part of the new family through her charm and wit.

For the next seven years between 1880 and 1887 Stevenson searched in vain for a place of residence suitable to his state of health. He spent his summers at various places in Scotland and England, including Westbourne, Dorset, a residential area in Bournemouth. There he lived in a dwelling he renamed Skerryvore after a lighthouse, the tallest in Scotland, built by his uncle Alan Stevenson many years earlier.

For his winters, he escaped to sunny France, and lived at Davos Platz and the Chalet de Solitude at Hyeres, where, for a time, he enjoyed almost complete happiness.

“I have so many things to make life sweet for me,” he wrote, “it seems a pity I cannot have that other one thing — health. But though you will be angry to hear it, I believe, for myself at least, what is is best. I believed it all through my worst days, and I am not ashamed to profess it now.”

In spite of his ill health he produced the bulk of his best known work: Treasure Island, his first widely popular book; Kidnapped; The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the story which established his wider reputation; and two volumes of verse, A Child’s Garden of Verses and Underwoods. At Skerryvore he gave a copy of Kidnapped to his dear friend and frequent visitor, Henry James Jnr.

On the death of his father in 1887, Stevenson felt free to follow the advice of his physician to try a complete change of climate.

He started with his mother and family for Colorado; but after landing in New York they decided to spend the winter at Saranac Lake, in the Adirondacks. During the intensely cold winter Stevenson wrote a number of his best essays, including Pulvis et Umbra, he began The Master of Ballantrae, and lightheartedly planned, for the following summer, a cruise to the southern Pacific Ocean. “The proudest moments of my life,” he wrote, “have been passed in the stern-sheets of a boat with that romantic garment over my shoulders.”

In June 1888, Stevenson chartered the yacht Casco and set sail with his family from San Francisco. The vessel “plowed her path of snow across the empty deep, far from all track of commerce, far from any hand of help.”

The salt sea air and thrill of adventure for a time restored his health; and for nearly three years he wandered the eastern and central Pacific, visiting important island groups, stopping for extended stays at the Hawaiian Islands where he became a good friend of King David Kalakaua, with whom Stevenson spent much time.

Furthermore, Stevenson befriended the king’s niece Princess Victoria Kaiulani, who was of Scottish heritage. He also spent time at the Gilbert Islands, Tahiti and the Samoan Islands. During this period he completed The Master of Ballantrae, composed two ballads based on the legends of the islanders, and wrote The Bottle Imp. The experience of these years is preserved in his various letters and in The South Seas. A second voyage on the Equator followed in 1889 with Lloyd Osbourne accompanying them.

It was also from this period that one particular open letter stands as testimony to his activism and indignation at the pettiness of such ‘powers that be’ as a Presbyterian minister in Honolulu named Rev. Dr. Hyde. During his time in the Hawaiian Islands, Stevenson had visited Molokai and the leper colony there, shortly after the demise of Father Damien. When Dr. Hyde wrote a letter to a fellow clergyman speaking ill of Father Damien, Stevenson wrote a scathing open letter of rebuke to Dr. Hyde. Soon afterwards in April 1890 Stevenson left Sydney on the Janet Nicoll and went on his third and final voyage among the South Seas islands.

In 1890 he purchased four hundred acres (about 1.6 square kilometres) of land in Upolu, one of the Samoan islands. Here, after two aborted attempts to visit Scotland, he established himself, after much work, upon his estate, which he named Vailima (“Five Rivers”). Stevenson himself adopted the native name Tusitala (Samoan for “Story Writer”).

His influence spread to the natives who consulted him for advice, and he soon became involved in local politics. He was convinced the European officials appointed to rule the natives were incompetent, and after many futile attempts to resolve the matter, he published A Footnote to History.

This was such a stinging protest against existing conditions that it resulted in the recall of two officials, and Stevenson feared for a time it would result in his own deportation. When things had finally blown over he wrote a friend, “I used to think meanly of the plumber; but how he shines beside the politician!”

In addition to building his house and clearing his land and helping the natives in many ways, he found time to work at his writing. In his enthusiasm, he felt that “there was never any man had so many irons in the fire.” He wrote The Beach of Falesa, Catriona (titled David Balfour in the USA), The Ebb-Tide, and the Vailima Letters, during this period.

For a time during 1894 Stevenson felt depressed; he wondered if he had exhausted his creative vein and completely worked himself out. He wrote that he had “overworked bitterly”. He felt more clearly that, with each fresh attempt, the best he could write was “ditch water”.

He even feared that he might again become a helpless invalid. He rebelled against this idea: “I wish to die in my boots; no more Land of Counterpane for me. To be drowned, to be shot, to be thrown from a horse — ay, to be hanged, rather than pass again through that slow dissolution.”

He then suddenly had a return of his old energy and he began work on Weir of Hermiston. “It’s so good that it frightens me,” he is reported to have exclaimed. He felt that this was the best work he had done.

He was convinced, “sick and well, I have had splendid life of it, grudge nothing, regret very little … take it all over, damnation and all, would hardly change with any man of my time.” Without knowing it, he was to have his wish fulfilled.

During the morning of 3 December 1894, he had worked hard as usual on Weir of Hermiston. During the evening, while conversing with his wife and straining to open a bottle of wine, he suddenly exclaimed, “What’s that!” He then asked his wife, “Does my face look strange?” and collapsed beside her. He died within a few hours, probably of a cerebral haemorrhage, at the age of 44.

The natives insisted on surrounding his body with a watch-guard during the night, and on bearing their Tusitala upon their shoulders to nearby Mount Vaea and buried him on a spot overlooking the sea.