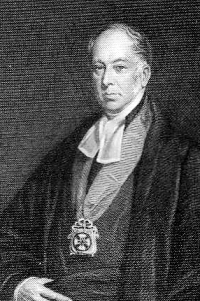

Richard Whately Archbishop of Dublin 1787 – 1863

January 20, 2009

Richard Whately

1787 – 1863 was an

English logician and theological writer who also served as Anglican

Archbishop of Dublin.

Richard Whately

1787 – 1863 was an

English logician and theological writer who also served as Anglican

Archbishop of Dublin.

Richard Whately was a staunch defender of homeopathy, and he wrote many letters in support of homeopathy. Whately also supported Charles Thomas Pearce when he was so unjustly accused by Thomas Wakley (Life and correspondence of Richard Whately, D.D.: late Archbishop of Dublin, Volume 2. Elizabeth Jane Whately. Longmans, Green, and Co., 1866. Multiple pages).

Richard Whately investigated the work of mesmerist Richard Dillon Tennant (1793-1856) of Belfast, who claimed to have healed very many persons with Apostolic mesmerism (Anon, List of the members, officers, and professors, [etc.] with the reports of the visitors for 1849]* (_Royal Institution of Great Britain. 1850). Page 34. See also Anon, _The Gentleman’s magazine, and historical review, Volume 201_,_ _Obituary notice for Richard Dillon Tennant of Albany Street, Regents Park,__ (_J.H. and J. Parker, 1856). Page 522. See also George Barth, [The Mesmerist’s Manual of Phenomena and Practice*](http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8XayXAu2JY8C&printsec=frontcover&dq=george+h+Barth&hl=en&sa=X&ei=GC6WUbX4NLCw7Abu_IHgCQ&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=george%20h%20Barth&f=false), (H. Balliere 1851, reprinted by Health Research Books, 1 Jan 1998)).

Richard Whately gave Richard Dillon Tennant an autographed attestation in support of his healing powers (Swedenborg Archive K124 [a] 1st Letter dated 12.4.1849 from Garth Wilkinson to Emma Marsh Wilkinson).

Whately was the Vice President of the London Homeopathic Hospital in 1850, and he left instructions for his treatment by homeopathy in the event of loss of speech or reason.

Whately was attended in his last illness by William Barclay Browne Scriven, a Dublin homeopath, who also received advice via telegraph from William Henderson.

William Barclay Browne Scriven explained that Richard Whately was converted to homeopathy when his favourite dog, given up by alopathic vets, was cured by homeopath Karl Sutton.

William Barclay Browne Scriven treated Whately for a senile gangrene in his gouty leg with mercurius 6c, belladonna and hyoscymus. William Barclay Browne Scriven also observed the effects of a left sided stroke some six years previously.

William Henderson’s homeopathic advice and William Barclay Browne Scriven’s treatment seemed to prevent the gangrene spreading further up Whately’s leg.

Whatley’s wife Elizabeth was also a good friend of Frederick Hervey Foster Quin.

Richard Whately was a friend of Charles Darwin, and he assisted Joseph Kidd in his work during the Irish potato famine.

The homeopathic hospital in Smyrna, was also supported by: Arthur Algernon Capell 6th Earl of Essex, Lord Lovaine MP (Algernon George Percy 6th Duke of Northumberland), James Gambier 1st Baron Gambier, George Wyndham 1st Baron Leconfield, Colonel Taylor, Edmund Gardiner Fishbourne, Robert Grosvenor 1st Baron Ebury, Richard Whately Archbishop of Dublin, Henry Charles FitzRoy Somerset 8th Duke of Beaufort, Arthur Wellesley 1st Duke of Wellington, James Hamilton 1st Duke of Abercorn, and 18 other members of the House of Lords, 43 Peer’s sons, Baronets and Members of Parliament, 17 Generals, 33 Field Officers, 43 other Officers of the Army, 2 Admirals, 15 Captains of the navy, 65 Clergymen, 45 Justices of the Peace, Barristers and Solicitors, and 314 Bankers, Merchants and others.

Richard Whately obtained double second class honours and the prize for the English essay; in 1811 he was elected Fellow of Oriel, and in 1814 took holy orders.

During his residence at Oxford he wrote his tract, Historic Doubts relative to Napoleon Bonaparte, a clever jeu d’ésprit directed against excessive scepticism as applied to the Gospel history.

After his marriage in 1821 he settled in Oxford, and in 1822 was appointed Bampton lecturer. The lectures, On the Use and Abuse of Party Spirit in Matters of Religion, were published in the same year.

In August 1823 he moved to Halesworth in Suffolk, but in 1825, having been appointed principal of St. Alban Hall, he returned to Oxford. He found much to reform there, and left it a different place.

In 1825 he published a series of Essays on Some of the Peculiarities of the Christian Religion, followed in 1828 by a second series On some of the Difficulties in the Writings of St Paul, and in 1830 by a third On the Errors of Romanism traced to their Origin in Human Nature.

While he was at St Alban Hall (1826) the work appeared which is perhaps most closely associated with his name - his treatise on Logic, originally contributed to the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana, in which he raised the study of the subject to a new level. It gave a great impetus to the study of logic throughout Britain. A similar treatise on Rhetoric, also contributed to the Encyclopaedia, appeared in 1828.

He was initially on friendly terms with John Henry Newman, but they fell out as the divergence in their views became apparent; Newman later spoke of his Catholic University as continuing in Dublin the struggle against Whately which he had commenced at Oxford.

In 1829 Whately was elected to the professorship of political economy at Oxford in succession to Nassau William Senior. His tenure of office was cut short by his appointment to the Archbishopric of Dublin in 1831.

He published only one course of Introductory Lectures (1832), but one of his first acts on going to Dublin was to endow a chair of political economy in Trinity College Dublin.

Whately’s appointment by Charles Grey 2nd Earl Grey, to the see of Dublin came as a great surprise to everybody, for though a decided Liberal, Whately had stood aloof from political parties, and ecclesiastically his position was that of an Ishmaelite fighting for his own hand.

The Evangelicals regarded him as a dangerous latitudinarian on the ground of his views on Catholic emancipation, the Sabbath question, the doctrine of election, and certain quasi-Sabellian opinions he was supposed to hold about the character and attributes of Christ, while his view of the church was diametrically opposed to that of the High Church party, and from the beginning he was the determined opponent of what was afterwards called the Tractarian movement.

The appointment was challenged in the House of Lords, but without success.

In Ireland it was unpopular among the Protestants, for the reasons mentioned and as being the appointment of an Englishman and a Whig. Whately’s bluntness and his lack of a conciliatory manner prevented him from eradicating these prejudices. At the same time he met with determined opposition from his clergy.

He attempted to establish a national and non-sectarian system of education. He enforced strict discipline in his diocese; and he published a statement of his views on the Sabbath (Thoughts on the Sabbath, 1832). He took a small place at Redesdale, just outside Dublin, where he could garden. Questions of tithes, reform of the Irish church and of the Irish Poor Laws, and, in particular, the organization of national education occupied much of his time. He discussed other public questions, for example, the subject of transportation and the general question of secondary punishments.

In 1837 he wrote his well-known handbook of Christian Evidences, which was translated during his lifetime into more than a dozen languages. At a later period he also wrote, in a similar form, Easy Lessons on Reasoning, on Morals, on Mind and on the British Constitution. Among his other works may be mentioned Charges and Tracts (1836), Essays on Some of the Dangers to Christian Faith (1839), The Kingdom of Christ (1841).

He also edited Bacon’s Essays, Paley’s Evidences and Paley’s Moral Philosophy. His scheme of religious instruction for Protestants and Catholics alike was carried out for a number of years , but in 1852 it broke down owing to the opposition of the new Catholic archbishop of Dublin, and Whately felt himself constrained to withdraw from the Education Board.

From the beginning Whately was a keen sighted observer of the condition of Ireland question, and gave offence by supporting state endowment of the Catholic clergy. During the terrible years of 1846 and 1847 the archbishop and his family tried to alleviate the miseries of the people.

From 1856 onwards symptoms of decline began to manifest themselves in a paralytic affection of the left side. Still he continued the active discharge of his public duties till the summer of 1863, when he was prostrated by an ulcer in the leg, and after several months of acute suffering he died on 8 October 1863.

Of interest:

Augustus Clissold dedicated his book The practical nature of the doctrines and alleged revelations contained in the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg to Richard Whately),