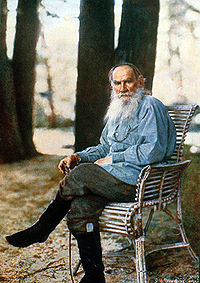

Leo Nikolayevich Tolstoy 1828 – 1910

February 25, 2009

Count Lev

Nikolayevich Tolstoy 1828 –

1910 was a Russian writer widely regarded as one of the greatest of all

novelists.

Count Lev

Nikolayevich Tolstoy 1828 –

1910 was a Russian writer widely regarded as one of the greatest of all

novelists.

Tolstoy wrote about homeopathy in War and Peace *(begun 1862), [The Cossacks, Sevastopol, the Invaders and Other Stories](http://books.google.com/books?id=GXr56wgEeqYC&pg=RA1-PA137&dq=tolstoy+homeopath&lr=&ei=o5WlSdnDApzAMty4wOUP#PRA1-PA137,M1), and in [The Death of Ivan Ilyich](http://books.google.com/books?lr=&ei=CZOlSb_tEIOUMp3rnIQO&id=yiN8AAAAIAAJ&dq=tolstoy+homeopath&q=homeopath&pgis=1#search_anchor). Tolstoy’s wife Sopia wrote about homeopathy in her diaries, and Sergei Tolstoy also writes about homeopathy in his [Tolstoy Remembered*](http://books.google.com/books?lr=&ei=QZmlSfrHC5ykkQTl5-WJDg&id=ZCY8AAAAMAAJ&dq=tolstoy+homeopath&q=homeopathy&pgis=1#search_anchor).

Tolstoy was influenced by Henry David Thoreau, and he was a friend of Anton Chekhov, and Fyodor Dostoevsky, and his friend Ivan Turgenev also wrote about homeopathy in his Phantoms and Other Stories, and in_ Father’s and Sons_.

Tolstoy also met Charles William Daniel, Rosalie Slaughter Morton, and Alice Bunker Stockham.

Leo Tolstoy was born August 28, 1828, at Yasnaya Polyana, Central Russia. The Tolstoys are a well-known family of old Russian nobility; Tolstoy was connected to the grandest families of Russian aristocracy; Alexander Pushkin was his fourth cousin.

Tolstoy’s childhood was spent between Moscow and Yasnaya Polyana, in a family of three brothers and a sister. He lost his mother when he was two, and his father when he was nine. His subsequent education was in the hands of his aunt, Madame Ergolsky…

In 1844, Tolstoy began studying law and Oriental languages at Kazan University, where teachers described him as “both unable and unwilling to learn.” He found no meaning in further studies and left the university in the middle of a term.

In 1849 he settled down at Yasnaya Polyana, where he attempted to be useful to his peasants but soon discovered the ineffectiveness of his uninformed zeal. From the very beginning, his diary reveals an insatiable thirst for a rational and moral justification of life, a thirst that forever remained a ruling force in his mind. The same diary was his first experiment in forging a technique of psychological analysis which was to become his principal literary weapon.

Tolstoy’s first literary effort was a translation of A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy. Sterne’s influence on his early works was substantial, although he subsequently denigrated him as “a devious writer”.

In 1851, he attempted a more ambitious and more definitely creative kind of writing, his first short story “A History of Yesterday”. In the same year, sick of his seemingly empty and useless life in Moscow, which brought heavy gambling debts, he went to the Caucasus, where he joined an artillery unit garrisoned in the Cossack part of Chechnya, as a volunteer of private rank, but of noble birth (junker).

In 1852 he completed his first novel Childhood and sent it to Nikolai Nekrasov for publication in the Sovremennik. Although Tolstoy was annoyed with the publishing cuts, the story had immediate success and gave Tolstoy a definite place in Russian literature.

In Sevastopol he wrote the battlefield observations Sevastopol Sketches, widely viewed as his first approach to the techniques to be used so effectively in War and Peace. Appearing as they did in the Sovremennik monthly while the siege of Sevastopol was still on, the stories greatly increased the general interest in their author.

In fact, the Tsar Alexander II was known to have said in praise of the author of the work, “Guard well the life of that man.” Soon after the abandonment of the fortress, Tolstoy went on leave of absence to St. Petersburg and Moscow. The following year he left the army.

The years 1856–61 were passed between Petersburg, Moscow, Yasnaya, and foreign countries. In 1857 (and again in 1860-61) he traveled abroad and returned disillusioned by the selfishness and materialism of European bourgeois civilization, a feeling expressed in his short story Lucerne and more circuitously in Three Deaths.

As he drifted towards a more oriental worldview with Buddhist overtones, Tolstoy learned to feel himself in other living creatures. He started to write Kholstomer, which contains a passage of interior monologue by a horse…

These years after the Crimean War were the only time in Tolstoy’s life when he mixed with the literary world. He was welcomed by the littérateurs of Petersburg and Moscow as one of their most eminent fellow craftsmen.

As he confessed afterwards, his vanity and pride were greatly flattered by his success, but he did not get on with them. He was too much of an aristocrat to like this semi-Bohemian intelligentsia. All the structure of his mind was against the grain of the progressive Westernizers, epitomized by Ivan Turgenev, who was widely considered the greatest living Russian author of the period. Ivan Turgenev, who was in many ways Tolstoy’s opposite, was also one of his strongest admirers; he called Tolstoy’s 1862 short novel The Cossacks “the best story written in our language”.

Tolstoy did not believe in Westernized progress and culture, and liked to tease Ivan Turgenev with outspoken or cynical statements. His lack of sympathy with the literary world culminated in a resounding quarrel with Ivan Turgenev in 1861, to the extent of challenging him to a duel, but to whom he apologized afterwards.

This incident is characteristic and revelatory of Tolstoy’s character, with its profound impatience of others’ assumed superiority and their perceived lack of intellectual honesty. The only writers with whom he remained friends were the conservative “landlordist” Afanasy Fet and the democratic Slavophile Nikolay Strakhov, both of them entirely out of tune with the main current of contemporary thought.

In 1859 he started a school for peasant children at Yasnaya, followed by 12 others, whose ground breaking libertarian principles Tolstoy described in his 1862 essay, “The School at Yasnaya Polyana”. He also authored a great number of stories for peasant children. Tolstoy’s educational experiments were short lived, but as a direct forerunner to A. S. Neill’s Summerhill School, the school at Yasnaya Polyana can justifiably be claimed to be the first example of a coherent theory of libertarian education.

In 1862 Tolstoy published a pedagogical magazine,_ Yasnaya Polyana_, in which he contended that it was not the intellectuals who should teach the peasants, but rather the peasants, the intellectuals.

He came to believe that he was undeserving of his inherited wealth, and gained renown among the peasantry for his generosity. He would frequently return to his country estate with vagrants whom he felt needed a helping hand, and would often dispense large sums of money to street beggars while on trips to the city.

In 1861 he accepted the post of Justice of the Peace, a magistrature that had been introduced to supervise the carrying out of the Emancipation reform of 1861.

Meanwhile his insatiable quest for moral stability continued to torment him. He had now abandoned the wild living of his youth, and thought of marrying. In 1856 he made his first unsuccessful attempt to marry Mlle Arseniev.

In 1860 he was profoundly affected by the death of his brother Nicholas. Although he had lost his parents and guardian aunts during his childhood, Tolstoy considered the death of his brother to be his first encounter with the inevitable reality of death. After these reverses, Tolstoy reflected in his diary that at 34, no woman could love him, since he was too old and ugly. In 1862, at last, he proposed to Sofia Andreyevna Behrs and was accepted. They were married on 24 September of the same year.

Tolstoy’s marriage is one of the two most important landmarks in his life, the other being his conversion. Once he entertained a passionate and hopeless aspiration after that whole and unreflecting “natural” state which he found among the peasants, and especially among the Cossacks in whose villages he had lived in the Caucasus. His marriage gave him an escape from unrelenting self-questioning. It was the gate towards that more stable and lasting “natural state”. Family life, and an unreasoning acceptance of and submission to the life to which he was born, now became his religion.

For the first 15 years of his married life he lived in a blissful state of confidently satisfied life, whose philosophy is expounded in War and Peace. Sophie Behrs, almost a girl when he married her and 16 years his junior, proved an ideal wife and mother and mistress of the house. On the eve of their marriage, Tolstoy gave her his diaries detailing his sexual relations with female serfs; the character of Levin in Anna Karenina behaves similarly, asking his fiancée Kitty to read his diaries and learn of his faults. Together they had 12 children, five of whom died in their childhoods.

Sophie was, moreover, a devoted help to her husband in his literary work; she acted as copyist of War and Peace, copying the manuscript seven times from beginning to end. The family fortune was prosperous, owing to Tolstoy’s efficient management of his estates and to the sales of his works, making it possible to provide adequately for the increasing family.

Soon after A Confession became known, Tolstoy began, at first against his will, to attract disciples. The first of these was Vladimir Chertkov, an ex-officer of the Horse Guards and founder of the Tolstoyans…

Tolstoy also established contact with certain sects of Christian communists and anarchists, like the Dukhobors. Despite his unorthodox views and support for Henry David Thoreau’s doctrine of civil disobedience, Tolstoy was unmolested by the government, solicitous to avoid negative publicity abroad.

Only in 1901 did the Synod excommunicate him. This act, widely but rather unjudiciously resented both at home and abroad, merely registered a matter of common knowledge – that Tolstoy had ceased to be a follower of the Orthodox Church.

As his reputation among people of all classes grew immensely, a few Tolstoyan communes formed throughout Russia in order to put into practice Tolstoy’s religious doctrines. And, by the last two decades of his life, Tolstoy enjoyed a place in the world’s esteem that had not been held by any man of letters since the death of Voltaire.

Yasnaya Polyana became a new Ferney – or even more than that, almost a new Jerusalem. Pilgrims from all parts flocked there to see the great old man.

But Tolstoy’s own family remained hostile to his teaching, with the exception of his youngest daughter Alexandra Tolstaya. His wife especially took up a position of decided opposition to his new ideas. She refused to give up her possessions and asserted her duty to provide for her large family.

Tolstoy renounced the copyright of his new works but had to surrender his landed property and the copyright of his earlier works to his wife. The later years of his married life have been described by biographer A. N. Wilson as some of the unhappiest in literary history.

Tolstoy was remarkably healthy for his age, but fell seriously ill in 1901 and had to live for a long time in Gaspra and Simeiz, Crimea. Still, he continued working and never showed any sign of diminished capacity.

Ever more oppressed by the apparent contradiction between his preaching of communism and the easy life he led under the regime of his wife, full of a growing irritation against his family, which was urged on by Chertkov, he finally left Yasnaya, in the company of his daughter Alexandra and his doctor, for an unknown destination.

After some restless and aimless wandering he headed for a convent where his sister was the mother superior but had to stop at Astapovo junction. There he was laid up in the stationmaster’s house and died, apparently of cold, on November 20, 1910. He was buried in a simple peasant’s grave in a wood 500 meters from Yasnaya Polyana. Thousands of peasants lined the streets at his funeral.