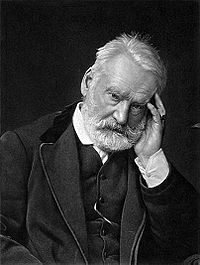

Victor Marie Hugo 1802 – 1885

February 26, 2009

Victor Marie

Hugo 1802 – 1885 was a

French poet, playwright, novelist, essayist, visual artist, statesman,

human rights activist and exponent of the Romantic movement in France.

Victor Marie

Hugo 1802 – 1885 was a

French poet, playwright, novelist, essayist, visual artist, statesman,

human rights activist and exponent of the Romantic movement in France.

Victor Hugo’s hero Francois Rene Vicomte de Chateaubriand was a homeopathic supporter, and his mistress Juliette Drouet told him in a letter dated 11.3.1852 that ‘… no homeopathy could cure… ’ her heartache after their separation (Juliette Drouet, Victoria Tietze Larson, Evelyn Blewer (Eds.), My beloved Toto: letters from Juliette Drouet to Victor Hugo, 1833-1882, (SUNY Press, 6 Oct 2005). Page 141). Juliette Drouet consulted homeopath Paul Ferdinand Gachet.

Victor Hugo was a friend of Charles Pierre Baudelaire, Louis Hector Berlioz, Sarah Bernhardt,** **Paul Cezanne, Benjamin Disraeli, Alexandre Dumas, Gustave Flaubert, Theophile Gautier, David Ferdinand Koreff, Franz Liszt, Victor Schoelcher, Jules Verne, Emile Zola,

Victor Hugo was an antivivisectionist. Victor Hugo’s granddaughter Jeanne Daudet married the son of Jean Martin Charcot.

Victor Hugo’s brother in law Paul Foucher was a friend of Alfred de Musset.

The poet Theophile Gautier, for instance, received hashish samples from Moreau de Tours. In 1843 he described extensively a self experienced hashish intoxication in the Paris newspaper La Presse under the title ‘Le Club des Hachichins’. The club of hashish eaters, of which Gauthier was one of the founders, had regular meetings in Hôtel Pimodan on the Seine island of St Louis.

He and Charles Pierre Baudelaire shared a penthouse in the hotel for several years. Other prominent club members were Alexandre Dumas and Honore Daumier. Further well known contemporaries such as Honore de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and Victor Hugo participated occasionally.

However, he was forced into exile during the reign of Napoleon III - he lived briefly in Brussels during 1851; in Jersey from 1852 to 1855; and in Guernsey from 1855 to 1870 and again in 1872-1873. There was a general amnesty in 1859; after that, his exile was by choice.

Hugo’s early childhood was marked by great events. The century prior to his birth saw the overthrow of the Bourbon Dynasty in the French Revolution, the rise and fall of the First Republic, and the rise of the First French Empire and dictatorship under Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon Bonaparte was proclaimed Emperor two years after Hugo’s birth, and the Bourbon Monarchy was restored before his eighteenth birthday.

The opposing political and religious views of Hugo’s parents reflected the forces that would battle for supremacy in France throughout his life: Hugo’s father was a high ranking officer in Napoleon’s army, an atheist republican who considered Napoleon a hero; his mother was a staunch Catholic Royalist who is believed to have taken General Victor Lahorie as her lover, who was executed in 1812 for plotting against Napoleon Bonaparte.

Since Hugo’s father, Joseph, was an officer, they moved frequently and Hugo learned much from these travels. On his family’s journey to Naples, he saw the vast Alpine passes and the snowy peaks, the magnificently blue Mediterranean, and Rome during its festivities. Though he was only nearly six at the time, he remembered the half year long trip vividly. They stayed in Naples for a few months and then headed back to Paris.

Sophie followed her husband to posts in Italy (where Léopold served as a governor of a province near Naples) and Spain (where he took charge of three Spanish provinces). Weary of the constant moving required by military life, and at odds with her unfaithful husband, Sophie separated temporarily from Léopold in 1803 and settled in Paris.

Thereafter she dominated Hugo’s education and upbringing. As a result, Hugo’s early work in poetry and fiction reflect a passionate devotion to both King and Faith. It was only later, during the events leading up to France’s 1848 Revolution, that he would begin to rebel against his Catholic Royalist education and instead champion Republicanism and Freethought.

Like many young writers of his generation, Hugo was profoundly influenced by Francois Rene Vicomte de Chateaubriand, the famous figure in the literary movement of Romanticism and France’s preëminent literary figure during the early 1800s.

In his youth, Hugo resolved to be “Chateaubriand or nothing,” and his life would come to parallel that of his predecessor in many ways. Like Francois Rene Vicomte de Chateaubriand, Hugo would further the cause of Romanticism, become involved in politics as a champion of Republicanism, and be forced into exile due to his political stances.

The precocious passion and eloquence of Hugo’s early work brought success and fame at an early age. His first collection of poetry (Nouvelles Odes et Poésies Diverses) was published in 1824, when Hugo was only twenty two years old, and earned him a royal pension from Louis XVIII. Though the poems were admired for their spontaneous fervor and fluency, it was the collection that followed two years later in 1826 (Odes et Ballades) that revealed Hugo to be a great poet, a natural master of lyric and creative song.

Young Victor fell in love and against his mother’s wishes, became secretly engaged to his childhood friend Adèle Foucher (1803-1868). Unusually close to his mother, it was only after her death in 1821 that he felt free to marry Adèle (in 1822). They had their first child Léopold in 1823, but the boy died in infancy. Hugo’s other children were Léopoldine (28 August 1824), Charles (4 November 1826), François-Victor (28 October 1828) and Adèle (24 August 1830).

Hugo published his first novel the following year (Han d’Islande, 1823), and his second three years later (Bug-Jargal, 1826). Between 1829 and 1840 he would publish five more volumes of poetry (Les Orientales, 1829; Les Feuilles d’automne, 1831; Les Chants du crépuscule, 1835; Les Voix intérieures, 1837; and Les Rayons et les ombres, 1840), cementing his reputation as one of the greatest elegiac and lyric poets of his time.

Victor Hugo’s first mature work of fiction appeared in 1829, and reflected the acute social conscience that would infuse his later work. Le Dernier jour d’un condamné (The Last Day of a Condemned Man) would have a profound influence on later writers such as Albert Camus, Charles Dickens, and Fyodor Dostoevsky. __

Claude Gueux, a documentary short story about a real life murderer who had been executed in France, appeared in 1834, and was later considered by Hugo himself to be a precursor to his great work on social injustice, Les Misérables.

But Hugo’s first full length novel would be the enormously successful Notre Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame), which was published in 1831 and quickly translated into other languages across Europe. One of the effects of the novel was to shame the City of Paris to undertake a restoration of the much neglected Cathedral of Notre Dame, which was attracting thousands of tourists who had read the popular novel. The book also inspired a renewed appreciation for pre-renaissance buildings, which thereafter began to be actively preserved.

Hugo began planning a major novel about social misery and injustice as early as the 1830s, but it would take a full 17 years for his most enduringly popular work, Les Misérables, to be realized and finally published in 1862. The author was acutely aware of the quality of the novel and publication of the work went to the highest bidder.

The Belgian publishing house Lacroix and Verboeckhoven undertook a marketing campaign unusual for the time, issuing press releases about the work a full six months before the launch. It also initially published only the first part of the novel (“Fantine”), which was launched simultaneously in major cities. Installments of the book sold out within hours, and had enormous impact on French society.

The critical establishment was generally hostile to the novel; Hyppolyte Taine found it insincere, Barbey d’Aurevilly complained of its vulgarity, Gustave Flaubert found within it “neither truth nor greatness,” the Goncourts lambasted its artificiality, and Charles Pierre Baudelaire

- despite giving favorable reviews in newspapers - castigated it in private as “tasteless and inept.”

Nonetheless, Les Misérables proved popular enough with the masses that the issues it highlighted were soon on the agenda of the French National Assembly. Today the novel remains popular worldwide, adapted for cinema, television and musical stage to an extent equaled by few other works of literature.

The shortest correspondence in history is between Hugo and his publisher Hurst & Blackett in 1862. It is said Hugo was on vacation when Les Misérables (which is over 1200 pages) was published. He telegraphed the single-character message ’?’ to his publisher, who replied with a single ’!‘.

Hugo turned away from social/political issues in his next novel, Les Travailleurs de la Mer (Toilers of the Sea), published in 1866. Nonetheless, the book was well received, perhaps due to the previous success of Les Misérables.

Dedicated to the channel island of Guernsey where he spent 15 years of exile, Hugo’s depiction of Man’s battle with the sea and the horrible creatures lurking beneath its depths spawned an unusual fad in Paris: Squids. From squid dishes and exhibitions, to squid hats and parties, Parisiennes became fascinated by these unusual sea creatures, which at the time were still considered by many to be mythical. The word used in Guernsey to refer to squid (pieuvre, also sometimes applied to octopus) was to enter the French language as a result of its use in the book.

Hugo returned to political and social issues in his next novel, L’Homme Qui Rit (The Man Who Laughs), which was published in 1869 and painted a critical picture of the aristocracy. However, the novel was not as successful as his previous efforts, and Hugo himself began to comment on the growing distance between himself and literary contemporaries such as Gustave Flaubert and Emile Zola, whose realist and naturalist novels were now exceeding the popularity of his own work.

His last novel, Quatrevingt-treize (Ninety-Three), published in 1874, dealt with a subject that Hugo had previously avoided: the Reign of Terror during the French Revolution. Though Hugo’s popularity was on the decline at the time of its publication, many now consider Ninety-Three to be a work on par with Hugo’s better known novels.

After three unsuccessful attempts, Hugo was finally elected to the Académie française in 1841, solidifying his position in the world of French arts and letters. Thereafter he became increasingly involved in French politics as a supporter of the Republic form of government.

He was elevated to the peerage by King Louis Philippe in 1841 and entered the Higher Chamber as a pair de France, where he spoke against the death penalty and social injustice, and in favour of freedom of the press and self government for Poland. He was later elected to the Legislative Assembly and the Constitutional Assembly, following the 1848 Revolution and the formation of the Second Republic.

When Napoleon III seized complete power in 1851, establishing an anti parliamentary constitution, Hugo openly declared him a traitor to France. He relocated to Brussels, then Jersey, and finally settled with his family on the channel island of Guernsey at Hauteville House, where he would live in exile until 1870.

While in exile, Hugo published his famous political pamphlets against Napoleon III, Napoléon le Petit and Histoire d’un crime. The pamphlets were banned in France, but nonetheless had a strong impact there. He also composed some of his best work during his period in Guernsey, including Les Misérables, and three widely praised collections of poetry (Les Châtiments, 1853; Les Contemplations, 1856; and La Légende des siècles, 1859).

He convinced the government of Queen Victoria to spare the lives of six Irish people convicted of terrorist activities and his influence was credited in the removal of the death penalty from the constitutions of Geneva, Portugal and Colombia.

Although Napoleon III granted an amnesty to all political exiles in 1859, Hugo declined, as it meant he would have to curtail his criticisms of the government. It was only after Napoleon III fell from power and the Third Republic was proclaimed that Hugo finally returned to his homeland in 1870, where he was promptly elected to the National Assembly and the Senate.

He was in Paris during the siege by the Prussian army in 1870, famously eating animals given to him by the Paris zoo. As the siege continued, and food became ever more scarce, he wrote in his diary that he was reduced to “eating the unknown.”

Because of his concern for the rights of artists and copyright, he was a founding member of the Association Littéraire et Artistique Internationale, which led to the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works.

Hugo’s religious views changed radically over the course of his life. In his youth, he identified as a Catholic and professed respect for Church hierarchy and authority. From there he evolved into a non-practising Catholic, and expressed increasingly violent anti catholic and anti clerical views.

He dabbled in Spiritualism during his exile (where he participated also in seances), and in later years settled into a Rationalist Deism similar to that espoused by Voltaire. When a census-taker asked Hugo in 1872 if he was a Catholic, he replied, “No. A Freethinker”.

Hugo never lost his antipathy towards the Roman Catholic Church, due largely to what he saw as the Church’s indifference to the plight of the working class under the oppression of the monarchy; and perhaps also due to the frequency with which Hugo’s work appeared on the Pope’s list of “proscribed books” (Hugo counted 740 attacks on Les Misérables in the Catholic press).

On the deaths of his sons Charles and François Victor, he insisted that they be buried without crucifix or priest, and in his will made the same stipulation about his own death and funeral. However, although Hugo believed Catholic dogma to be outdated and dying, he never directly attacked the institution itself. He also remained a deeply religious man who strongly believed in the power and necessity of prayer.

Hugo’s Rationalism can be found in poems such as Torquemada (1869, about religious fanaticism), The Pope (1878, violently anti clerical), Religions and Religion (1880, denying the usefulness of churches) and, published posthumously, The End of Satan and God (1886 and 1891 respectively, in which he represents Christianity as a griffin and Rationalism as an angel). “Religions pass away, but God remains”, Hugo declared. Christianity would eventually disappear, he predicted, but people would still believe in “God, Soul, and the Power.”

Although Hugo’s many talents did not include exceptional musical ability, he nevertheless had a great impact on the music world through the endless inspiration that his works provided for composers of the 19th and 20th century.

Hugo himself particularly enjoyed the music of Gluck and Weber and greatly admired Ludwig von Beethoven, and rather unusually for his time, he also appreciated works by composers from earlier centuries such as Palestrina and Monteverdi.

Two famous musicians of the 19th century were friends of Hugo: Louis Hector Berlioz and Franz Liszt. The latter played Beethoven in Hugo’s home, and Hugo joked in a letter to a friend that thanks to Franz Liszt’s piano lessons, he learned how to play a favourite song on the piano – even though only with one finger!

Hugo also worked with composer Louise Bertin, writing the libretto for her 1836 opera La Esmeralda which was based on Hugo’s novel Notre Dame de Paris. Although for various reasons this beautiful and original opera closed soon after its fifth performance and is little known today, it has been recently enjoying a revival, both in a piano/song concert version by Franz Liszt at the Festival international Victor Hugo et Égaux 2007 and in a full orchestral version to be presented in July 2008 at Le Festival de Radio France et Montpellier Languedoc Roussillon.

Well over one thousand musical compositions have been inspired by Hugo’s works from the 1800s until the present day. In particular, Hugo’s plays, in which he rejected the rules of classical theatre in favour of romantic drama, attracted the interest of many composers who adapted them into operas.

More than one hundred operas are based on Hugo’s works and among them are Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia (1833), Verdi’s Rigoletto (1851) and Ernani (1844), and Ponchielli’s La Gioconda (1876).

Hugo’s novels as well as his plays have been a great source of inspiration for musicians, stirring them to create not only opera and ballet but musical theatre such as Notre Dame de Paris and the ever popular Les Misérables, London West End’s longest running musical.

Additionally, Hugo’s beautiful poems have attracted an exceptional amount of interest from musicians, and numerous melodies have been based on his poetry by composers such as Louis Hector Berlioz, Bizet, Faure, Franck, Lalo, Franz Liszt, Massenet, Saint Saens, Rachmaninov and Wilhelm Richard Wagner…

When Hugo returned to Paris in 1870, the country hailed him as a national hero. Despite his popularity Hugo lost his bid for reelection to the National Assembly in 1872. Within a brief period, he suffered a mild stroke, his daughter Adèle’s internment in an insane asylum, and the death of his two sons. (His other daughter, Léopoldine, had drowned in a boating accident in 1843, and his wife Adèle had died in

- His faithful mistress, Juliette Drouet, died in 1883, only two years before his own death.)

Despite his personal loss, Hugo remained committed to the cause of political change. On 30 January 1876 Hugo was elected to the newly created Senate. His last phase in his political career is considered a failure. Hugo took on a stubborn role and got little done in the Senate.

In February 1881 Hugo celebrated his 79th birthday. To honor the fact that he was entering his eightieth year, one of the greatest tributes to a living writer was held. The celebrations began on the 25th when Hugo was presented with a Sèvres vase, the traditional gift for sovereigns.

On the 27th one of the largest parades in French history was held. Marchers stretched from Avenue d’Eylau, down the Champs Élysées, and all the way to the center of Paris. The paraders marched for six hours to pass Hugo as he sat in the window at his house. Every inch and detail of the event was for Hugo; the official guides even wore cornflowers as an allusion to Cosette’s song in Les Misérables.

Victor Hugo’s death on 22 May 1885, at the age of 83, generated intense national mourning. He was not only revered as a towering figure in French literature, but also internationally acknowledged as a statesman who had helped preserve and shape the Third Republic and democracy in France. More than two million people joined his funeral procession in Paris from the Arc de Triomphe to the Panthéon, where he was buried. He shares a crypt within the Panthéon with Alexandre Dumas and Emile Zola.

Many are not aware that Hugo was almost as prolific in the visual arts as he was in literature, producing more than 4,000 drawings in his lifetime. Originally pursued as a casual hobby, drawing became more important to Hugo shortly before his exile, when he made the decision to stop writing in order to devote himself to politics. Drawing became his exclusive creative outlet during the period 1848-1851.

Hugo worked only on paper, and on a small scale; usually in dark brown or black pen and ink wash, sometimes with touches of white, and rarely with color. The surviving drawings are surprisingly accomplished and “modern” in their style and execution, foreshadowing the experimental techniques of Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism.

He would not hesitate to use his children’s stencils, ink blots, puddles and stains, lace impressions, “pliage” or folding (i.e. Rorschach blots), “grattage” or rubbing, often using the charcoal from match sticks or his fingers instead of pen or brush. Sometimes he would even toss in coffee or soot to get the effects he wanted. It is reported that Hugo often drew with his left hand or without looking at the page, or during Spiritualist séances, in order to access his unconscious mind, a concept only later popularized by Sigmund Freud.

Hugo kept his artwork out of the public eye, fearing it would overshadow his literary work. However, he enjoyed sharing his drawings with his family and friends, often in the form of ornately handmade calling cards, many of which were given as gifts to visitors when he was in political exile.

Some of his work was shown to, and appreciated by, contemporary artists such as Vincent van Gogh and Ferdinand Victor Eugene Delacroix; the latter expressed the opinion that if Hugo had decided to become a painter instead of a writer, he would have outshone the artists of their century.