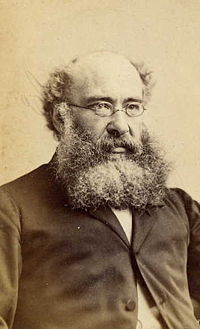

Anthony Trollope 1815 – 1882

February 27, 2009

Anthony

Trollope 1815 – 1882

became one of the most successful, prolific and respected English

novelists of the Victorian era.

Anthony

Trollope 1815 – 1882

became one of the most successful, prolific and respected English

novelists of the Victorian era.

Anthony Trollope and his family were advocates of homeopathy (N. John Hall, Trollope: a biography, (Clarendon Press, 14 Nov 1991). Page 116).

Anthony Trollope was a friend of Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, George MacDonald, Laurence Oliphant, Bessie Rayner Parkes, John Ruskin, William Makepeace Thackeray.

Trollope’s friend Julian Hawthorne was the son of Nathaniel Hawthorne and Sophia Peabody.

Nonetheless, he came from a genteel background, with connections to the landed gentry, and so wished to educate his sons as gentlemen and for them to attend Oxford or Cambridge. The disparity between his family’s social background and its poverty would be the cause of much misery to Anthony Trollope during his boyhood.

Born in London, Anthony attended Harrow School as a day boy for three years from the age of seven, as his father’s farm lay in that neighbourhood. After a spell at a private school, he followed his father and two older brothers to Winchester College, where he remained for three years. He returned to Harrow as a day boy to reduce the cost of his education.

Trollope had some very miserable experiences at these two public schools. They ranked as two of the most élite schools in England, but Trollope had no money and no friends, and was bullied a great deal. At the age of twelve, he fantasized about suicide. However, he also daydreamed, constructing elaborate imaginary worlds.

In 1827, his mother Frances Trollope moved to America with Trollope’s three younger siblings, where she opened a bazaar in Cincinnati, which proved unsuccessful. Thomas Trollope joined them for a short time before returning to the farm at Harrow, but Anthony stayed in England throughout.

His mother returned in 1831 and rapidly made a name for herself as a writer, soon earning a good income. His father’s affairs, however, went from bad to worse. He gave up his legal practice entirely and failed to make enough income from farming to pay rents to his landlord Lord Northwick. In 1834 he fled to Belgium to avoid arrest for debt. The whole family moved to a house near Bruges, where they lived entirely on Frances’s earnings. In 1835, Thomas Trollope died.

While living in Belgium, Anthony worked as a Classics usher (a junior or assistant teacher) in a school with a view to learning French and German, so that he could take up a promised commission in an Austrian cavalry regiment, which had to be cut short at six weeks. He then obtained a position as a civil servant in the British Post Office through one of his mother’s family connections, and returned to London on his own. This provided a respectable, gentlemanly occupation, but not a well paid one.

Trollope lived in boarding houses and remained socially awkward; he referred to this as his “hobbledehoyhood”. He made little progress in his career until the Post Office sent him to Ireland in 1841. He married an Englishwoman named Rose Heseltine in 1844. They lived in Ireland until 1859, when they moved back to England.

Despite the calamity of the Great Famine in Ireland, Trollope wrote of his time in Ireland in his own autobiography:

“It was altogether a very jolly life that I led in Ireland. The Irish people did not murder me, nor did they even break my head. I soon found them to be good humoured, clever - the working classes very much more intelligent than those of England - economical and hospitable.” His professional role as a post office surveyor brought him into contact with Irish people. Trollope began writing on the numerous long train trips around Ireland he had to take to carry out his postal duties. Setting very firm goals about how much he would write each day, he eventually became one of the most prolific writers of all time. He wrote his earliest novels while working as a Post Office inspector, occasionally dipping into the “lost letter” box for ideas.

Significantly, many of his earliest novels have Ireland as their setting — natural enough given his background, but unlikely to enjoy warm critical reception, given the contemporary English attitudes towards Ireland. It has been pointed out by critics that Trollope’s view of Ireland separates him from many of the other Victorian novelists. Some critics claim that Ireland did not influence Trollope as much as his experience in England, and that the society in Ireland harmed him as a writer, especially since Ireland was experiencing the famine during his time there. Such critics were dismissed as holding bigoted opinions against Ireland and did not reflect Trollope’s true attachment to the country.

Trollope wrote three novels about Ireland. Two were written during the famine, while the third deals with the famine as a theme (The Macdermots of Ballycloran, The Landleaguers and Castle Richmond respectively). The Macdermots of Ballycloran was written while he was staying in the village of Drumsna, County Leitrim.Two short stories deal with Ireland (“The O’Conors of Castle Conor, County Mayo” and “Father Giles of Ballymoy” It has been argued by some critics that these works seek to unify an Irish and British identity, instead of viewing the two as distinct. Even as an Englishman in Ireland, Trollope was still able to attain what he saw as essential to being an “Irish writer”: possessed, obsessed, and “mauled” by Ireland.

The reception of the Irish works left much to be desired. Henry Colburn wrote to Trollope, “It is evident that readers do not like novels on Irish subjects as well as on others”. In particular, magazines such as New Monthly Magazine, which wrote reviews that attacked the Irish for their actions during the famine, were representative of the dismissal by English readers to any work written about the Irish.

Trollope himself wrote, about Phineas Finn’s identity as an Irishman:

"There was nothing to be gained by the peculiarity, and there was an added difficulty in obtaining sympathy and affection for a politician belonging to a nationality whose politics are not respected in England. But in spite of this Phineas succeeded."

By the mid 1860s, Trollope had reached a fairly senior position within the Post Office hierarchy. Postal history credits him with introducing the pillar box (the ubiquitous bright red mail box) in the United Kingdom.

He had by this time also started to earn a substantial income from his novels. He had overcome the awkwardness of his youth, made good friends in literary circles, and hunted enthusiastically.

He left the Post Office in 1867 to run for Parliament as a Liberal candidate in 1868. After he lost, he concentrated entirely on his literary career. While continuing to produce novels rapidly, he also edited the St Paul’s Magazine, which published several of his novels in serial form.

His first major success came with The Warden (1855) — the first of six novels set in the fictional county of “Barsetshire” (often collectively referred to as the Chronicles of Barsetshire), usually dealing with the clergy. The comic masterpiece Barchester Towers (1857) has probably become the best-known of these. Trollope’s other major series, the Palliser novels, concerned itself with politics, with the wealthy, industrious Plantagenet Palliser and his delightfully spontaneous, even richer wife Lady Glencora usually featuring prominently (although, as with the Barsetshire series, many other well developed characters populated each novel).

Trollope’s popularity and critical success diminished in his later years, but he continued to write prolifically, and some of his later novels have acquired a good reputation. In particular, critics generally acknowledge the sweeping satire The Way We Live Now (1875) as his masterpiece. In all, Trollope wrote forty seven novels, as well as dozens of short stories and a few books on travel.

Anthony Trollope died in London in 1882. His grave stands in Kensal Green Cemetery, near that of his contemporary Wilkie Collins. C. P. Snow wrote a biography of Trollope, published in 1975, called Trollope: His Life and Art.

In 1871, Trollope made his first trip to Australia, arriving in Melbourne in July, with his wife and their cook. The trip was made to visit their younger son, Frederic, who was a sheep farmer near Grenfell, New South Wales. He wrote his novel Lady Anna during the voyage.

He spent a year and two days “descending mines, mixing with shearers and rouseabouts, riding his horse into the loneliness of the bush, touring lunatic asylums, and exploring coast and plain by steamer and stagecoach”. Despite this, the Australian press was uneasy, fearing he would misrepresent Australia in his writings. This fear was based on rather negative writings about America by his mother, Frances Trollope, and by Charles Dickens.

On his return Trollope published a book, Australia and New Zealand (1873). It contained both positive and negative comments. On the positive side included finding a comparative absence of class consciousness, and praising aspects of Perth, Melbourne, Hobart and Sydney. However, he was negative about Adelaide’s river, the towns of Bendigo and Ballarat, and the Aboriginal people. What most angered the Australian papers, though, were his comments “accusing Australians of being braggarts”.

When Trollope returned to Australia in 1875 to help his son close down his failed farming business, he found that the resentment created by his bragging accusations remained and, when he died in 1882, Australian papers still “smouldered”. In their obituaries they referred yet again to his accusations, and refused to fully praise or recognise his achievements…

Of interest:

Thomas Trolloppe MD Cantab was a homeopath who practiced at 9 Maze Hill, St. Leonard ‘s on Sea in 1881.