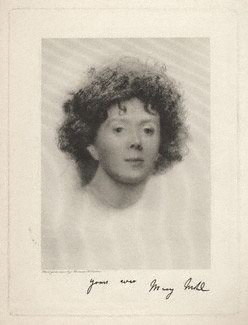

Mary Elizabeth Clarke Mohl 1793 - 1883

April 21, 2009

Mary Elizabeth

Clarke Mohl 1793 - 1883 was a British socialite who

organised

a popular and influential social

salon

in Paris.

Mary Elizabeth

Clarke Mohl 1793 - 1883 was a British socialite who

organised

a popular and influential social

salon

in Paris.

Mary Clarke Mohl was known as ‘Clarkey’ and ‘she knew everyone’ including Alexander Bain, Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, Robert Browning, Lord Byron and his wife Annabella, Margaret Fuller, William and Mary Howitt and their daughter Anna Mary Howitt, Ottilie von Goethe (daughter in law of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe), Francois Pierre Guillaume Guizot, Harriet Martineau, Florence Nightingale, Nassau William Senior, Marie Henri Beyle, Stendhal, Alfred Lord Tennyson, and many others.

Mary was married to Julius von Mohl, and she was the sister in law of Hugo von Mohl and Robert von Mohl.

From Cecil Woodham Smith, Florence Nightingale, 1820-1910, (McGraw-Hill, 1951). Pages 18-21.

Her personal appearance was odd. She was very small, with the figure and height of a child; her eyes were startlingly large and bright, and at a period when women brushed their hair smoothly she wore hers over her forehead in a tangle of curls. Francois Pierre Guillaume Guizot, who was devoted to her, said that she and his Yorkshire terrier patronized the same coiffeur…

Mary Clarke’s mother was an invalid who could not tolerate the English climate. She left for France in 1801 with her mother, Mrs Hay, and Mary (who was born in 1793). Mary was educated in a convent in the south and returned to Paris in 1813, after which she never again lived for more than months at a time in England.

Mary became bilingual and neither exactly French nor exactly English in manner… But Mary Clarke’s strangeness also allowed her a freedom of action not easily open to respectable unmarried women… In a more approving comment, Jean Jacques Ampere, the son of the scientist and her lifelong friend (and livelong devotee of Madame Recamier) wrote of her relation to Francois Rene Vicomte de Chateaubriand:

“She is a charming combination of French sprightliness and English originality; but I think the French element predominates. She was the delight of the grand ennuye; her expressions were entirely her own; and he more than once made use of them in his writings.”

Her French was as original as the turn of her mind, exquisite in quality; but savouring more of the last century than of our own. Through her grandmother’s connections with David Hume and other Scottish intellectuals and through her family relations (Lord Dalrymple was her cousin; Frewen Turner MP, of Cold Overton in Leicestershire, her brother in law) Mary Clarke had access to some French intellectuals and was sought out by some of the visiting English (the Nightingales, Elizabeth Eastlake, Alfred Lord Tennyson, Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell, Augusta Stanley).

I assume that the Scottish connection provided her first opportunity to meet the “jeune France” who formed her earliest group of friends. But her main attraction seems to have been personal. Her first salons, between 1815 and 1838, in the rue Bonaparte and then in the Abbaye au Bois, were run for the benefit of her mother, a woman of lively mind and sociable disposition, interested in politics, who because of her illness could not easily go about in the city.

They consisted of young men beginning their careers (Jean Jacques Ampere, Julius von Mohl, Edgar Quintet, Louis Adolphe Thiers, Francois Pierre Guillaume Guizot, the Thierry brothers) and some older friends, like Claude Charles Fauriel, the Provencal scholar, who valued an informal meeting place with lively discussion.

Her fortuitous connection with Madame Recamier (I think through Jean Jacques Ampere) and with Francois Rene Vicomte de Chateaubriand gave her access to a more exclusively literary salon and also extended the scope of her own.

After the death of her mother, and of Claude Charles Fauriel, to whom she had been romantically devoted for years (he had been devoted to Condorcet’s widow), Mary married Julius von Mohl (in 1847; she was 54, he 47) and continued her salon in the rue du Bac until after the Franco Prussian war. Julius von Mohl was a German orientalist who did much to establish French pre-eminence in Near Eastern archaeology and who translated from Persian and Chinese manuscripts which Mary edited after his death, as she edited Claude Charles Fauriel’s Provencal manuscripts after his.

Mary Clarke herself comments on the change in style of the salon during her lifetime from the very simple forms of entertainment like her own to the more elaborate manner of the end of the century.

Of her own early life she wrote: “I lived some weeks with two ladies, mother and daughter, the latter was wondrous clever. They dined at five, drank tea at eight, and they were not out of the pale of humanity, though not fashionable. Now, since that time, literary people have dwindled into the fancy of being fashionable and it has ruined their society.

“No doubt these were the remains-I may say the tail-of the days when Dr. Johnson was the delight of all London at Mrs. Thrale’s, the brewer’s wife. It was after dinner, and not at all late - eight, nine, or ten, I suppose.

“Those evenings in the last century left a good long tail among people of moderate means and sociable lively brains. But being invited to a tea party at nine was still feasible and common in 1820 to 1830; not among fashionable, but among cultivated people - lawyers, doctors, and literary folk … There’s no society in London now - none, none!”

Very little money was required for the kind of salon Mary Clarke ran, in all its manifestations. She relied on her personal idiosyncrasy; on the particular Parisian social arrangements which were less domestic than those of London but also had fewer man’s clubs; on the eclat of Paris for the English tourist; and on the predominance of Paris for the French themselves…

Mary Clarke retained her vigour and her discipline into old age. She was devastated by the death of her husband in 1876, but in 1879 Ernest Renan wrote in a letter of “this excellent person about ninety years of age, who has more esprit and gaiety than ever, who speaks of 1815 and 1820 as if it were yesterday”

… and she herself wrote to Mary Simpson in 1881, “I am a poor creature, but I run about and am as alert as ever”.

She died on 15 May 1883, aged ninety.

Mary write A Life of Madame Recamier.