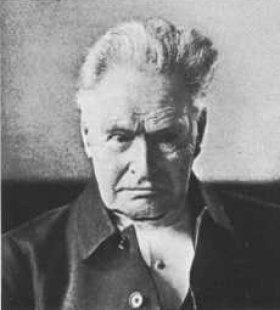

Edmund Beckett Lord Grimthorpe 1816 – 1905

May 27, 2009

Edmund

Beckett, 1st Baron

Grimthorpe

QC 1816 – 1905 known previously as Sir Edmund Beckett, 5th Baronet

and Edmund Beckett Denison was a lawyer, amateur horologist, and

architect.

Edmund

Beckett, 1st Baron

Grimthorpe

QC 1816 – 1905 known previously as Sir Edmund Beckett, 5th Baronet

and Edmund Beckett Denison was a lawyer, amateur horologist, and

architect.

In 1851 he designed the mechanism for the clock of the Palace of Westminster, responsible for the chimes of Big Ben.

Edmund Beckett was an enthusiastic and ardent devotee of homeopathy (Anon, Homeopathic Directory, (Homeopathic Publishing Company, 1898). Page 66. See also Anon, Southern Journal of Homoeopathy, Volume 1, (Southern Journal Publishing Company, 1888). Pages 34 and 125), and he wrote to The Times in 1888 to protest against the prejudice of the allopathic physicians in dismissing Kenneth William Millican, which resulted in a month long battle of words in The Times, and the whole affair was written up in John Henry Clarke’s Odium medicum and homeopathy.

In 1874, Edmund Becket Lord Grimthorpe stepped in to assist George Dunn in the financing of the The St. James Homeopathic Hospital Doncaster. The hospital building was subsequently sold on 1st March 1880 by Edmund Beckett Grimthorpe.

In 1887, Edmund Becket Lord Grimthorpe, Chairman of the Governing Body, proposed homeopaths and homeopathic supporters as nominees to the Margaret Street Infirmary, and the Board of the Hospital clearly stated that homeopaths were not ineligible, and John Beckett, John Roberson Day, Kenneth William Millican, and Charles Lloyd Tuckey, were duly appointed,

http://www.homeoint.org/morrell/londonhh/dailpres.htm In the 40 years ending 1890 during which homeopathy had been practised in England, the columns of the daily Press had but rarely been opened to discussions upon it.

This prolonged silence with regard to a matter that was so intimately connected with the vital interests of the whole community, was broken by The Times in 1881, at the period when Benjamin Disraeli (who was a patient of homeopath Joseph Kidd) lay dangerously, ill; and again in December, 1887, on account of the high handed action of the committee of a newly established institute called the Queen’s Jubilee Hospital against Kenneth William Millican, who had been duly elected its surgeon for throat diseases.

The only grievance the committee of the Jubilee Hospital had against Kenneth William Millican was that he belonged to an institution where liberty of opinion on therapeutics was accorded to the medical officers.

The committee of the Jubilee Hospital could not find any fault with the practice of Kenneth William Millican, but they, nevertheless expelled him and appointed another in his place. Kenneth William Millican brought all action against the committee for wrongful dismissal and got judgment in his favour, which judgment, however, was reversed on appeal.

Lord Grimthorpe in a letter to The Times called attention to the bigotry of the committee of the Jubilee Hospital in dismissing an able and competent member of their medical staff for no other cause than his acceptance of a post in another institution where liberty of opinion and practice was allowed to its medical officers.

This conduct he characterised as a flagrant instance of the Odium medicum. A considerable number of representatives of allopathy replied to the letter, protesting that Lord Grimthorpe was altogether wrong in attributing to their side and Odium medicum, and unconsciously proving his accusation up to the hilt by the very strong language they used against homeopathy and its adherents.

After the controversy had gone on for ten days the editor of The Times joined in the fray with a leading article in favour of homeopathy.

This elicited an outburst of still more violent denunciations of homeopathy.

When the discussion had raged in the columns of The Times for another fortnight, the editor closed it with another leading article claiming that Lord Grimthorpe had been successful in establishing his original contention.

The good example set by The Times in treating of homeopathy with the respect and deference it merited was followed by many newspapers and periodicals, both at home and abroad.

The subject excited great interest, even in Australia, and the beneficial effect that this prolonged discussion had on the proper understanding of homeopathy by the general community is felt even at the present day.

Our facetious friend Punch published (January 28, 1888) a humorous account of the battle of the rival schools, in which the partisan of the globule was represented as having the best of the fray.

This was accompanied by a

cartoon by Edward Linley Sambourne, which by the courtesy of the publishers is here reproduced.

From John Henry Clarke’s Odium medicum and homeopathy: “I will now quote the case of the homeopathic cure of an animal.

“It is taken from The Times of Jan. 6, 1888, being communicated in a letter to the editor in the course of the Odium medicum correspondence, afterwards published in a book from under the title of Odium medicum and homeopathy…

Meissonier’s Testimony in Favour of Homeopathy. To the Editor of The Times:

“I was studying painting a few years ago with Meissonier, whose valuable dog - which had been given to him by his great friend Alexandre Dumas - was stuck with paralysis in its hind quarters; it had also its neck twisted.

“I had long studied Homeopathy for my own use, and my little globules were the subject of much good humoured fun to Meissonier and his friends and family, who did not believe in them at all.

“The dog in question was condemned to death by a great ‘vet.’ In Paris, who attended to Meissonier’s very valuable horses, as will be seen in the enclosed testimony.

“The same evening I was dining with him and his family, and the dog was in the room - a subject of much lamentation - when, in his sudden and animated manner, he challenged me to cure it with ‘my Homeopathy’

“I accepted the challenge and gave the dog at once in their presence a single dose of Rhus tox, of a rather high dilution.

“The Next morning I was at work with him alone in his garden studio before breakfast, when his clever and energetic daughter came rushing into the studio as if the house were on fire, crying out that ‘the dog walked.’

“We ran out of the studio - Meissonier with his brush in his mouth and his large palette on his thumb, in his earnest eagerness about everything that freshly caught his attention- and there was the animal running about on its four legs as strongly as ever.

“It still had its neck twisted, however, and I was much puzzled to know how to proceed with my patient. I then perceived that its coat was rough and staring. Here came in one of the great principles of Homeopathy - that every symptom must be taken into account - and the proper remedy at once suggested itself.

“I gave it two doses of Arsenicum 3X; the dog quite recovered, and is I believe, alive and well to this day. Yours faithfully, A Pupil of Meissonier.”

At the close of this controversy on 20th January 1888, The London Times wrote ‘… So great has been the interest excited by the correspondence, that the editor has been unable to publish only a fraction of the letters sent him. The original contention was that an Odium Medicum exists, exactly analogous to the Odium Theologicum of a less enlightened age, and no less capable of blinding men… (Federal Vanderburgh et al (Eds), Pamphlets - homeopathic, Volume 17, (1844 [onwards]). Page 30)‘.

Edmund Beckett was a relative of William Thomas Denison, who was also an advocate of homeopathy.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Beckett,_1st_Baron_Grimthorpe Lord Grimthorpe was also responsible for rebuilding the west front, roof, and transept windows of St Albans Cathedral at his own expense.

Although the building had been in need of repair, popular opinion at the time held that he had changed the cathedral’s character, even inspiring the creation and temporary popularity of the verb “to grimthorpe”, meaning to carry out unsympathetic restorations of ancient buildings.

Part of Beckett’s additions included statues of the four evangelists around the western door; the statue of St Matthew has Beckett’s face. He later turned his attentions to St Peter’s and then to St Michael’s Church, both in the same city.

In 1868 he worked with W H Crossland to design St Chad’s Church, Far Headingley in Leeds.

Edmund Beckett was born at Carlton Hall Nottinghamshire, England, and was the son of Sir Edmund Beckett, 4th Baronet. He studied at Eton and Trinity College, Cambridge, was made a Queen’s Counsel in 1854, and was created Baron Grimthorpe in 1886.

He is sometimes known as Edmund Beckett Denison; his father had taken the additional name Denison in 1816, but the son dropped it on his father’s death in 1874.

He married Fanny Catherine 1823 – 1901 daughter of John Lonsdale, 89th Bishop of Lichfield.

He died on 29 April 1905 after a fall, and is buried in the grounds of St Albans Cathedral.

Of interest:

George Bulmer was the Surgeon and Medical attendant of Christopher Beckett 1777 - 1847, an uncle of Edmund Beckett. George Bulmer was also the medical teacher of James John Garth Wilkinson in 1832:

See http://www.holytrinitymeanwood.org.uk/files/history.shtml: Miss Mary Beckett (1775 -1858) (twin sister of Sir John Beckett, 2nd Baronet [1775-1847]) and Miss Elizabeth Beckett (1781-1864). They were the daughters of Sir John Beckett 1st Baronet (1743-1826), Banker of Meanwood Park. The church was built in memory of their brother, Christopher Beckett (1777-1847), Banker, who had founded Meanwood National School in Green Road in 1840.

The Foundation Stone was laid on 20 May 1848 by William Beckett Denison, nephew of the founders. The Beckett sisters are buried in the Beckett mausoleum, the large stone structure at the east end of the churchyard.

The Parish Church of Meanwood was consecrated on 6 October 1849 and dedicated to The Holy and Undivided Trinity.

The church is a grade II listed building. The architect was William Railton (1801-1877). He was Architect to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners from 1838-1848 and also designed Nelson’s Column, Trafalgar Square, London, 1839-1842. He practised from Regent Street, London.

The Vicarage

The first vicarage, the ‘parsonage house’, was built in 1849 for the first incumbent, the Revd George Urquhart, on land which is now Parkside Green and was demolished in 1964. The new vicarage, at the end of Parkside Green, was built between 1964 and 1965 for the then new incumbent, the Revd J Stanley Dodd. It is interesting to note that the stone for the wall, which encloses the Memorial Rose Garden, built in 1965-1966, was from the old vicarage.

The Church Clock

The clock was added in 1850 - designed by Edmund Beckett Denison, QC, MP (who later became the 1st Baron Grimthorpe in 1886) nephew of Christopher, Mary and Elizabeth Beckett. He was a designer of clocks, inventing the gravity escapement which is used in turret clocks (the clock in St Stephen’s Tower, Westminster, which controls Big Ben was designed by G B Airy and Edmund Beckett Denison). The Meanwood clock was built by Edward John Dent (1790-1853) of London, a celebrated maker.

The Church Bells

Three bells were hung in the bell chamber in 1849, cast by Messrs John Taylor & Co of Loughborough, Leicestershire, the heaviest being the tenor bell. One bell was recast in 1885 when two more bells were added. The cost of the new bells and necessary alterations to the belfry (nearly £300) was borne by Mary Beckett, a niece of the founders.The bells weigh approximately 16 cwt, 14 cwt, 12 cwt, 10 cwt and 8 cwt each. In 1930 the bells needed new bearings and were given a quarter turn. It is understood that the Meanwood ring of five bells is the heaviest in Yorkshire.

Meanwood Stone

The Church and the ‘parsonage house’ were built with millstone grit from quarries owned by Messrs Daniel & Dunbar. The general contractor was Mr G Bridgart of Derby, who used local labour to do the building. Stone from the Meanwood/Weetwood area (Hustler was also a quarry owner) was also used to build Holy Trinity Church, Boar Lane (1772), the present Mill Hill Unitarian Chapel (1848), Meanwood Methodist Church (1881) and the Royal Dockyards and Pier at Dover.