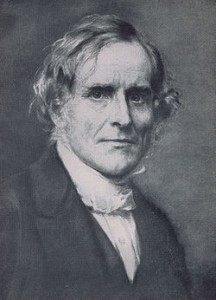

John Frederick Denison Maurice 1805 - 1872

May 29, 2012

John

Frederick Denison

Maurice (1805-1872),

often known as Frederick Denison

Maurice, was

an English theologian and Christian Socialist.

John

Frederick Denison

Maurice (1805-1872),

often known as Frederick Denison

Maurice, was

an English theologian and Christian Socialist.

[Frederick Denison Maurice](John Frederick Denison Maurice, often known as F. D. Maurice (29 August 1805-1 April 1872), was an English theologian and Christian Socialist.) was a friend of James John Garth Wilkinson (Robin Larsen, Emanuel Swedenborg: a continuing vision: a pictorial biography & anthology of essays & poetry, (Swedenborg Foundation, 1988). Page 132. ** **Thomas Carlyle’s circle included Henry James senior, John Stuart Mill, Alfred Lord Tennyson, George Lewes, Frederick Denison Maurice, Alexander Bain, and James John Garth Wilkinson). Denison was also a friend of Thomas Erskine.

In 1866, John Frederick Denison Maurice was an Occasional Lecturer at the Working Woman’s College at 29 Queen Square Bloomsbury. James John Garth Wilkinson was a subscriber to this college at this time (Anon, Second annual report of the council of teachers, London working women’s college, (1866). Page 2).

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Denison_Maurice Maurice was born at Normanston, Suffolk, the son of a Unitarian minister, and entered Trinity College, Cambridge in 1823, though only members of the Established Church were eligible to obtain a degree. Together with John Sterling (with whom he founded the Apostles’ Club) he migrated to Trinity Hall and obtained a first class degree in civil law in 1827; he then came to London and gave himself to literary work, writing a novel, Eustace Conway, or the Brother and Sister, and editing the London Literary Chronicle until 1830 and also, for a short time, the Athenaeum.

At this time Maurice was undecided about his religious opinions and he ultimately found relief in a decision to take a further university course and to seek Anglican ordination. Entering Exeter College, Oxford, he took a second class degree in classics in 1831. He was ordained in 1834 and, after a short curacy at Bubbenhall in Warwickshire, was appointed chaplain of Guy’s Hospital and became a leading figure in the intellectual and social life of London. From 1839 to 1841, he was editor of the Education Magazine. In 1840 he was appointed professor of English history and literature at King’s College London and to this post in 1846 was added the chair of divinity. In 1845 he was Boyle lecturer and Warburton lecturer. He held these chairs until 1853.

In 1853 he published Theological Essays; the opinions it expressed were viewed by R. W. Jelf, principal of King’s College, as being of unsound theology. He had previously been called on to clear himself from charges of heterodoxy brought against him in the Quarterly Review (1851) and had been acquitted by a committee of inquiry. He maintained with great conviction that his views were in accord with Scripture and the Anglican standards, but King’s College Council ruled otherwise and he was deprived of his professorships, although he received sympathy from friends and former pupils. Despite this, a chair at King’s College, the F.D. Maurice Professorship of Moral and Social Theology, now commemorates his contribution to scholarship. He resigned the chaplaincy at Guy’s Hospital for the chaplaincy of Lincoln’s Inn (1846–1860); later an offer to resign here was refused by the benchers. He held the incumbency of St. Peter’s, Vere Street from 1860 to 1869, where a further resignation offer was refused. He was engaged in a hot and bitter controversy with Henry Longueville Mansel (afterwards dean of St Paul’s), arising out of the latter’s 1858 Bampton lecture on reason and revelation.

His son Frederick Maurice edited “The Life of Frederick Denison Maurice Chiefley Told in His Own Letters” - Two volumes, Macmillan, 1884.

Maurice was involved with important educational initiatives. He helped found Queen’s College for the education of governesses in 1848. He was the leading light and one of the promoters and founders of The Working Men’s College (est. 1854), being its principal between 1854 and 1872. With Frances Martin he set up the Working Women’s College in 1874 [?he died in 1872?]. He strongly advocated the abolition of university tests (1853), and threw himself with great energy into all that affected the social life of the people. Certain abortive attempts at co-operation among working men, and the movement known as Christian Socialism, were the immediate outcome of his teaching. In 1866 Maurice was appointed Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy at Cambridge, and from 1870 to 1872 was incumbent of St Edward’s in that city. Many streets in London are named in F D Maurice’s honour, including Maurice Walk, a street in Hampstead Garden Suburb.

Maurice is honored with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) on April 1.

He was twice married, first to Anna Barton, a sister of John Sterling’s wife, secondly to a half-sister of his friend Archdeacon Hare. His son Major-General Sir John Frederick Maurice (1841-1912), became a distinguished soldier and one of the most prominent military writers of his time. Frederick Barton Maurice was a British General and writer, and like his grandfather F.D. Maurice, principal of The Working Men’s College (1922–1933).

Those who knew Maurice best were deeply impressed with the spirituality of his character. “Whenever he woke in the night,” says his wife, “he was always praying.” Charles Kingsley called him “the most beautiful human soul whom God has ever allowed me to meet with.” As regards his intellectual attainments we may set Julius Hare’s verdict “the greatest mind since Plato” over against John Ruskin’s “by nature puzzle-headed and indeed wrong-headed.”

While many “Broad Churchmen” were influenced by ethical and emotional considerations in their repudiation of the dogma of everlasting torment, Maurice was swayed by intellectual and theological arguments, and in questions of a more general liberty he often opposed the Liberal theologians. He had a wide metaphysical and philosophical knowledge which he applied to the history of theology. He was a strenuous advocate of ecclesiastical control in elementary education, and an opponent of the new school of higher biblical criticism, though so far an evolutionist as to believe in growth and development as applied to the history of nations.

As a preacher, his message was apparently simple; his two great convictions were the fatherhood of God, and that all religious systems which had any stability lasted because of a portion of truth which had to be disentangled from the error differentiating them from the doctrines of the Church of England as understood by himself. The prophetic, even apocalyptic, note of his preaching was particularly impressive. He prophesied “often with dark foreboding, but seeing through all unrest and convulsion the working out of a sure divine purpose.” Both at King’s College and at Cambridge Maurice gathered a following of earnest students. He encouraged the habit of inquiry and research, more valuable than his direct teaching.

As a social reformer, Maurice was before his time, and gave his eager support to schemes for which the world was not ready. The condition of the city’s poor troubled him; the magnitude of the social questions involved was a burden he could hardly bear. Working men of all opinions seemed to trust him even if their faith in other religious men and all religious systems had faded, and he had a power of attracting both the zealot and the outcast.

Not everyone however was appreciative of his sermons or company: CARLYLE LETTERS, Vol 10: Thomas Carlyle to John A. Carlyle ; 1 February 1838:

The Maurices are also wearisome, and happily rare; all invitations “to meet the Maurices” I, when it is any way possible, make a point of declining. Yet this very night I am “to dine with the Maurices” in Stimabiledom, and again on Saturday night “to meet the Maurices and Lady Lewis” there,—if mercy or good management prevent not. One of the most entirely uninteresting men of genius that I can meet with in society is poor Maurice to me. All twisted, screwed, wiredrawn; with such a restless sensitiveness; the uttermost inability to let Nature have fair play with him! I do not remember that a word ever came from him betokening clear recognition or healthy free sympathy with any thing. One must really let him alone; till the prayers one does always offer for him (purehearted, earnest, humane creature as he is) begin to take effect.

CARLYLE LETTERS, Vol 9: Jane W Carlyle to John Sterling ; 1 February 1837 Mr Morris (sic) we rarely see—nor do I greatly regret his absence; for to tell you the truth, I am never in his company without being attacked with a sort of paroxysm of mental cramp! he keeps one always with his wire-drawings and paradoxes as if one were dancing on the points of one’s toes (spiritually speaking)— And then he will help the kettle and never fails to pour it all over the milk pot and sugar bason [sic]!—

Oxford Book of Literary Anecdotes I went, as usual about this time, to hear F.D. Maurice preach at Lincoln’s Inn. I suppose I must have heard him, first and last, some thirty or forty times, and never carried away one clear idea, or even the impression that he had more than the faintest conception of what he himself meant.

Aubrey de Vere was quite right when he said that listening to him was like eating pea-soup with a fork, and Jowett’s answer was no less to the purpose, when I asked him what a sermon which Maurice had just preached at the University was about, and he replied—‘Well! all that I could make out was that today was yesterday, and this world the same as the next.