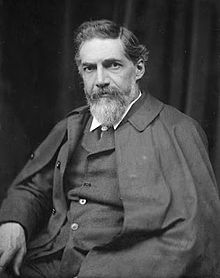

William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853-1942)

July 02, 2013

William

Matthew Flinders

Petrie (1853-1942) FRS,

’… c_ommonly known as Flinders Petrie, was an

English Egyptologistand a pioneer of systematic methodology

in archaeology and preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of

Egyptology in the United Kingdom, and excavated many of the most

important archaeological sites in Egypt. Some consider his most famous

discovery to be that of the Merneptah Stele, an opinion with which

Petrie himself concurred. Petrie developed the system of dating layers

based on pottery and ceramic findings._..’

William

Matthew Flinders

Petrie (1853-1942) FRS,

’… c_ommonly known as Flinders Petrie, was an

English Egyptologistand a pioneer of systematic methodology

in archaeology and preservation of artefacts. He held the first chair of

Egyptology in the United Kingdom, and excavated many of the most

important archaeological sites in Egypt. Some consider his most famous

discovery to be that of the Merneptah Stele, an opinion with which

Petrie himself concurred. Petrie developed the system of dating layers

based on pottery and ceramic findings._..’

Flinders Petrie’s father William was an ‘… enthusiastic homeopath…’ and his children were brought up with it (Joyce Tyldesley, Egypt: How A Lost Civilisation Was Rediscovered, (Random House, 31 Oct 2010). Page 139).

Flinders Petrie was a close friend of Florence Blakiston Attwood Mathews, the second daughter of James John Garth Wilkinson, and her husband Benjamin Attwood Mathews, who spent a good deal of time in Egypt with him:

‘… _Thank you, my dear friend, for your generous Secrets of the Nile. They will be made good use of, for my daughter has now a large Egyptian collection. Mr. Flinders Petrie, the explorer I think of Bubastis, is well known to her. And he proposes to spend next winter in London, determine to enter seriously on heiroglyphic lore… _(Swedenborg Archives K125 [15] letter dated 25.8.1989 from Garth Wilkinson to John Thomson)…’

From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flinders_Petrie ’…* __William Matthew Flinders Petrie was born in Maryon Road, Charlton, Kent, England, the son of William Petrie (1821–1908) and Anne (née Flinders (1812–1892). Anne was the daughter of Captain Matthew Flinders, surveyor of the Australian coastline, spoke six languages and was an Egyptologist. William Petrie was an electrical engineer who developed carbon arc lighting and later developed chemical processes for Johnson, Matthey & Co.*

Flinders was raised in a Christian household (his father being Plymouth Brethren), and was educated at home. He had no formal education. His father taught his son how to survey accurately, laying the foundation for his archaeological career. At the age of eight he was tutored in French, Latin, and Greek, until he had a collapse and was taught at home. He also ventured his first archaeological opinion aged eight, when friends visiting the Petrie family were describing the unearthing of Brading Roman villa in the Isle of Wight. The boy was horrified to hear the rough shovelling out of the contents, and protested that the earth should be pared away, inch by inch, to see all that was in it and how it lay. “All that I have done since,” he wrote when he was in his late seventies, “was there to begin with, so true it is that we can only develop what is born in the mind. I was already in archaeology by nature.”

On 26 November 1896 Petrie married Hilda Urlin (1871–1957) in London. They had two children, John (1907–1972) and Ann (1909–1989). They originally lived in Hampstead, where anEnglish Heritage blue plaque now stands on the building they lived in, 5 Cannon Place. In 1933, on retiring from his professorship, he moved permanently to Jerusalem, where he lived with Lady Petrie at the British School of Archaeology, then temporarily headquartered at the American School of Oriental Research (today the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research).

When he died in 1942, Petrie donated his head (and thus his brain) to the Royal College of Surgeons of London while his body was interred in the Protestant Cemetery on Mt. Zion. World War II was then at its height, and the head was delayed in transit. After being stored in a jar in the college basement, its label fell off and no one knew who the head belonged to. It was identified however, and is now stored, but not displayed, at the Royal College of Surgeons of London. The chair of Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at University College London was set up and funded in 1892 by a bequest of Amelia Edwards following her sudden death in that year. Petrie’s supporter since 1880, Edwards had instructed that he should be its first incumbent. He continued to excavate in Egypt after taking up the professorship, training many of the best archaeologists of the day. In 1913 Petrie sold his large collection of Egyptian antiquities to University College, London, where it is now housed in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology…’