Vladimir von Ditman 1842 - 1904

September 27, 2009

Vladimir von

Ditman 1842 - 1904 MD was a Russian orthodox physician who converted

to homeopathy against vituperous opposition from allopathic colleagues,

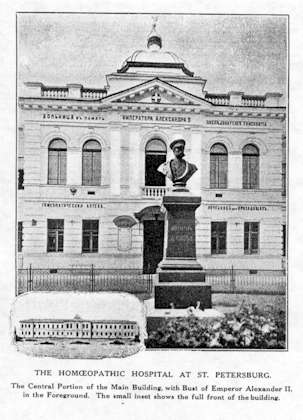

and who was granted a homeopathic hospital in St. Petersberg by Tsar

Alexander

III (Alexander

Kotok, M.D., The history of homeopathy in the Russian Empire until

World War I, as compared with other European countries and the USA:

similarities and

discrepancies, (On-line

version of the Ph.D. thesis improved and enlarged due to a special grant

of the Pierre Schmidt foundation 2001)).

Vladimir von

Ditman 1842 - 1904 MD was a Russian orthodox physician who converted

to homeopathy against vituperous opposition from allopathic colleagues,

and who was granted a homeopathic hospital in St. Petersberg by Tsar

Alexander

III (Alexander

Kotok, M.D., The history of homeopathy in the Russian Empire until

World War I, as compared with other European countries and the USA:

similarities and

discrepancies, (On-line

version of the Ph.D. thesis improved and enlarged due to a special grant

of the Pierre Schmidt foundation 2001)).

With thanks to Alexander Kotov:

Dr. Ditman also stressed that the conversion to homeopathy in Russia had been extremely difficult because of widely spread biases against homeopathy and for one’s fear of losing one’s position.

”[…] For a doctor who decides to convert to homeopathy, the official career is closed almost completely. Only if he hides his ‘heretical’ views from the medical authorities […] will he be allowed to stay at his workplace.

“On the contrary, if the doctor expresses his opinion concerning the superiority of homeopathy over allopathy openly, his verdict has already been signed: neither job, nor reward, nor promotion […], nor pension in old age.

“In brief, he has to sacrifice so many things that there have been only a few doctors who were prepared to follow this [homeopathic] method.”

Dr. von Ditman stressed that several important events throughout his life influenced his decision to convert to homeopathy. First of all, he was, at the age of eighteen, a witness to the terrible deaths of his two year old brother and five year old sister from diphtheria, whilst one doctor refused to treat these at all (“there is anyway no hope”) and the treatment prescribed by another doctor (cantharide ointment) transformed the torments of the sister into unbearable ones.

“During a long time I was under the strong impression of this terrible event. ‘Is medical science’ - I thought - ‘so powerless indeed?’ One half of the future generation has died, whilst medicine knows nothing and has no means to help! Finally, if there is no escape, why should one harass and torture a sick child so barbarously? Who needs these cantharides, etc., increasing the sufferings without procuring any relief!”

Secondly, when studying at Dorpat university, Ditman was bitterly dissatisfied with the situation of contemporary medicine. There was no clear explanation why patients were receiving this, that or any other drug, but mainly empirical allegations.

The confirmation of diagnosis by section was considered as a “triumph of science”, whilst the useful medicines for almost all diseases were absent. Von Ditman was fortunate to hear three lectures on homeopathy delivered by the internist Prof. Weirich.

The latter had recognized that medicine benefited to an enormous extent from homeopathy (giving non-mixed medicines in as small as possible doses, the importance of diet).

Nevertheless, homeopathy as a doctrine was ridiculed by the professor. But these refutations of homeopathy “were purely theoretical and doctrinal. Neither experiment, nor observation! Why cannot minimal doses […] be effective? Why is the law of similarity absurd? All these [questions] remained unanswered”.

Moreover, when studying pharmacology, von Ditman became convinced that arbitrariness ruled in this most important section of medicine. Thus, when he met his relative, the homeopath, Anton von Hubbenett… he was rather prepared to accept a new teaching.

Finally von Ditman converted to homeopathy after the tincture of Ipecacuanha saved his dying baby, who was suffering from diarrhea.

“I have never before seen such a fast, such an impressive success of treatment. In such a serious disease as acute inflammation of stomach and guts of an eight month old baby, the baby recovered completely within 12 hours!”

In 1882, Tsar Alexander III supported Vladimir von Ditman in his request to treat diphtheria homeopathically with mercurius cyanatus, a request seconded by Tsar Alexander III’s Rear Admiral and Adjutant, Otton Richter,

In 1882, Tsar Alexander III passed Vladimir von Ditman’s proposal to the Medical Council. Thus, the latter had to reply.

The inquiry of Vladimir von Ditman was briefly cited in the “Decision” of the Medical Council, published in the official newspaper “Pravitel’stvennyi vestnik” (Government’s Herald).

“There have been families where three, four and five children died within several days. Allopathic doctors are almost powerless in the struggle with this terrible enemy; while having no reliable medicine at their disposal, they lost as much as more than a half of all their patients.

“Since this disease […] threatens to become a general disaster, I, Vladimir von Ditman, as a father and as a doctor, have no right to remain silent. I have become convinced after 12 years of homeopathic practice that there is a most reliable homeopathic medicine [for diphtheria].

“My personal observations have been verified by a large number of observations […] made by my colleagues.”

Vladimir von Ditman asked Tsar Alexander III to provide homeopaths with an appropriate department “of several dozens of beds” at some St. Petersburg hospital, where poor sick children would have been treated with homeopathic medicines.

As allopaths usually stressed that homeopaths misdiagnosed their patients, Vladimir von Ditman insisted that one of the “distinguished specialists” confirm the diagnosis of diphtheria.

”When analyzing the “Decision”, I would like to divide the latter into two parts. The first part dealt with the personality of von Ditman, whilst the second one dealt with the essence of von Ditman’s proposal. Both parts are approximately equal in size.

In the first part, the authors of the “Decision” tried, on the basis of Ditman’s books and pamphlets, to convince the reader that he was a total ignoramus in what they called science.

Mainly they pointed out some inaccuracies in Ditman’s definitions of that or other disease. As to the proposal itself, the Council repeated the old fables on the oceans of water needed to prepare the 30th dilution, which was considered by von Ditman as especially effective in the treatment of diphtheria.

Again, the Council insisted that homeopathic treatment cannot be effective on the ground of theoretical allegations and speculations only; the mere thought of a possible examination of the method was refused with indignation.

The Medical Council […] concluded: 1. Mr. Ditman does possess neither medical, nor even the preparatory training needed to observe the sick.

- His allegations concerning a reliable healing effect of mercurius cyanatus in diphtheria, do not deserve any consideration.

- From a scientific point of view, any attempt at proving the efficiency of homeopathic grains of mercurius cyanatus cannot represent any interest.

[…]

- It would be desirable to attract the attention of the censure institutions to the publications of Mr. Ditman […] as the advertising instructions contained in them can deceive the public.

Signed: The Chairman: E. Pelikan; […]; Advisory members: N. Kozlov, N. Zdekauer, […], Y. Chistovich […].

One should pay attention, that among the persons who signed the “Decision”, were

- The chairman Evgeny V. Pelikan (1824-1884), who was in the 1850s a physician in the “Exemplary hospital” created by Martin Wilhelm von Mandt … where pseudo-homeopathic (atomistic) treatment was provided.

- Profs. N. Kozlov and N. Zdekauer, who twenty years before had proposed their own program of “reconciliation” with homeopaths.

- Yacov Chistovich, whose especially suspicious anti-homeopathic diary is analyzed in the chapter “Homeopathic facilities”.

I have to mention that the authors of the “Decision” did not propose any other treatment as an alternative to homeopathy. Corynebacterium diphtheriae was found by Klebs in 1883; in 1884 Loeffler succeeded to grow this pathogenic organism artificially, whilst a more or less reliable treatment was developed in the late 1880s and in the beginning of the 1890s.

The first successful treatment of diphtheria in Russia, based upon the latest scientific findings and technologies (I mean anti-diphtheric serum), was provided by Prof. Georgy Gabrichevsky (1860-1907) in a Moscow clinic in 1893-94, i.e., 11-12 years after the homeopaths had proposed their own method of treatment.

Thus, Russian regular medical profession rejected a possible treatment, be it scientific or not, sufficiently effective or not, without testing it, whilst “scientific” allopathic treatment was at that time non-existent.

The fact that allopaths, who enjoyed State support, were empowered to reject the proposals of the homeopaths without any practical examination, was traditionally an especially painful point of Russian homeopathy.

Nevertheless, both the lack of any reliable treatment of diphtheria and the understanding that the “Decision” was clearly written by a biased interest group, allowed the Red Cross to provide homeopaths with a unit at an allopathic hospital.

Then allopaths applied another tactics: they did not refer patients to the homeopathic unit and thus forced its closing (see the chapter “Homeopathic facilities”).