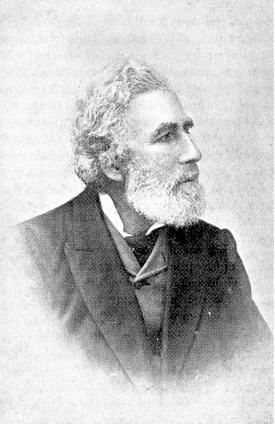

Charles Bradlaugh (1833-1891)

November 10, 2013

Charles

Bradlaugh (1833-1891)

was a political activist and one of the most famous

English atheists of the 19th

century. He founded the National Secular

Society in 1866.

Charles

Bradlaugh (1833-1891)

was a political activist and one of the most famous

English atheists of the 19th

century. He founded the National Secular

Society in 1866.

Charles Bradlaugh supported the Anti Compulsory Vaccination movement (Hilda Kean, London stories: personal lives, public histories, (Rivers Oram, 2004). Page 217). Bradlaugh also actively supported contraception, and he worked alongside homeopaths and supporters of homeopaths to do this.

It would be the Drysdale family and the homeopathic community, ably assisted by radical free thinkers, who would come out to support the embattled trio. Against the usual fierce and vitriolic storm of protest, the collaboration of Charles Bradlaugh and the Drysdale family, fully supported by the homeopathic press (Elizabeth K. Helsinger, _THE WOMAN QUESTION Social Issues, 1837-1883_, *(Manchester University Press, 1983). Page 219)), enabled the firm foundation of modern birth control to become a reality in Britain (Robert Jütte, [Contraception: A History*](http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=sqwMrennRsQC&pg=PA108&dq=charles+bradlaugh+drysdale&hl=en&sa=X&ei=9w19UreWD-qW0AXug4HwCw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=charles%20bradlaugh%20drysdale&f=false), (Polity, 12 May 2008). Page 108).

In America, Robert Dale Owen had promoted contraception in the 1820’s and Charles Knowlton had written about these ideas in his book The Fruits of Philosophy in 1832. Charles Bradlaugh had already published the British edition of Charles Knowlton’s The Fruits of Philosophy. _In 1854, George Drysdale wrote _The Elements of Social Science *(originally called *__Physical, Sexual and Natural Religion and published by Edward Truelove of 240 Strand), which was a publishing sensation in its day, and went through 35 editions between 1855 and 1905 and sold 80,000 copies. George Drysdale published his ideas in Charles Bradlaugh’s National Reformer, _alongside Bradlaugh’s defiant defence of George Drysdale’s book (Elizabeth K. Helsinger, *[THE WOMAN QUESTION Social Issues, 1837-1883](http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=6h28AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA218&dq=charles+bradlaugh+drysdale&hl=en&sa=X&ei=9w19UreWD-qW0AXug4HwCw&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=charles%20bradlaugh%20drysdale&f=false), *(Manchester University Press, 1983). Page 218)) in his own book Charles Bradlaugh, _Jesus, Shelley, and Malthus: Or, Pious Poverty and Heterodox Happiness_, (?date written, republished by Arden Library, 1979). _

_In 1877 Bradlaugh and Annie Wood Besant republished Charles Knowlton’s _The Fruits of Philosophy, with footnotes written by George Robert Drysdale to bring the physiology up to date (Martha Vicinus, Suffer and be Still: Women in the Victorian Age, (Indiana University Press, 1973). Page 39. See also Edward Royle, Radicals, Secularists, and Republicans: Popular Freethought in Britain, 1866-1915, (Manchester University Press, 1980). Page 15).

Bradlaugh and Annie Wood Besant were immediately charged with publishing Charles Knowlton’s *The Fruits of Philosophy (?_obscenity charges). The resultant trial was a National sensation, and it also included the prosecution of their elderly and very brave publisher Edward Truelove (1809-1899)*, who very rarely gets a mention in the reports of this trial (Stanley R. Ingman, Anthony E. Thomas, _Topias and Utopias in Health: Policy Studies_, (Walter de Gruyter, 1 Jan 1975). Page 28), and it is shameful that many historians repeatedly go for the ‘big names’ and ignore the brave men and women that surround them, including the homeopaths! What is also very shocking is the fact that the British Library’s copies of the editions published in 1872, 1875, 1886 of George Drysdale The Elements of Social Science _are listed as ‘destroyed’. The British Library copy of 1867 is listed as ‘missing’, though it is possible that the 1904 and 1905 copies are in the British Museum still (though thankfully, this is now available as an ebook! George Robert Drysdale, [The Elements of Social Science; Or, Physical, Sexual, and Natural Religion*](http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=zk8zAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=The+Elements+of+Social+Science+drysdale&hl=en&sa=X&ei=KSzUUO-aAYjK0QWV7oG4Dg&ved=0CDwQ6AEwAA), (Truelove, 256 Holborn, 1867)).

The Drysdale family and Annie Wood Besant founded the Malthusian League after the resolution of the famous Wood Bradlaugh trial in 1877. Annie Wood Besant is usually credited with the idea of founding the Malthusian League, though Charles Bradlaugh is also given credit for this too (S. Chandrasekhar, Reproductive Physiology and Birth Control: The Writings of Charles Knowlton and Annie Besant, (Transaction Publishers, 1 Jan 2002). Page 31). The truth is that both of these magnificent campaigners, together with Charles Robert Drysdale, founded the Malthusian League in 1877.

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Bradlaugh Born in Hoxton (an area in the East End of London), Bradlaugh was the son of a solicitor’s clerk. He left school at the age of eleven and then worked as an office errand-boy and later as a clerk to a coal merchant. After a brief spell as a Sunday school teacher, he became disturbed by discrepancies between the Thirty-nine Articles of the Anglican Church and the Bible. When he expressed his concerns, the local vicar, John Graham Packer, accused him of atheism and suspended him from teaching. He was thrown out of the family home and was taken in by Elizabeth Sharples Carlile, the widow of Richard Carlile, who had been imprisoned for printing Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason.

Soon Bradlaugh was introduced to George Holyoake, who organised Bradlaugh’s first public lecture as an atheist. At the age of 17, he published his first pamphlet, A Few Words on the Christian Creed. However, refusing financial support from fellow freethinkers, he enlisted as a soldier with the Seventh Dragoon Guards hoping to serve in India and make his fortune. Instead he was stationed in Dublin.

In 1853, he was left a legacy by a great-aunt and used it to purchase his discharge from the army. Bradlaugh returned to London in 1853 and took a post as a solicitor’s clerk. By this time he was a convinced freethinker and in his free time he became a pamphleteer and writer about “secularist” ideas, adopting the pseudonym “Iconoclast” to protect his employer’s reputation. He gradually attained prominence in a number of liberal or radical political groups or societies, including the Reform League, Land Law Reformers, and Secularists.

He was President of the London Secular Society from 1858. In 1860 he became editor of the secularist newspaper, the National Reformer, and in 1866 co-founded the National Secular Society, in which Annie Wood Besant became his close associate. In 1868, the Reformer was prosecuted by the British Government for blasphemy and sedition. Bradlaugh was eventually acquitted on all charges, but fierce controversy continued both in the courts and in the press.

A decade later (1876), Bradlaugh and Annie Wood Besant decided to republish the American Charles Knowlton’s pamphlet advocating birth control, The Fruits of Philosophy, or the Private Companion of Young Married People, whose previous British publisher had already been successfully prosecuted for obscenity. The two activists were both tried in 1877, and Charles Darwin [Darwin was a very close family friend of the Drysdale family] refused to give evidence in their defence. They were sentenced to heavy fines and six months’ imprisonment, but their conviction was overturned by the Court of Appeal on a legal technicality. The Malthusian League was founded as a result of the trial to promote birth control. He was a member of a Masonic lodge in Bolton, although he was later to resign due to the nomination of the Prince of Wales as Grand Master.

Bradlaugh was an advocate of trade unionism, republicanism, and women’s suffrage, and he opposed socialism. His anti-socialism was divisive, and many secularists who became socialists left the secularist movement because of its identification with Bradlaugh’s liberal individualism. He was a supporter of Irish Home Rule, and backed France during the Franco-Prussian War. He took a strong interest in India.

In 1880 Bradlaugh was elected Member of Parliament for Northampton. To take his seat and become an active Parliamentarian, he needed to signify his allegiance to the Crown and on 3 May Bradlaugh came to the Table of the House of Commons, bearing a letter to the Speaker “begging respectfully to claim to be allowed to affirm” instead of taking the religious Oath of Allegiance, citing the Evidence Amendment Acts of 1869 and 1870… On at least one occasion, Bradlaugh was escorted from the House by police officers. In 1883 he took his seat and voted three times before being fined £1,500 for voting illegally. A bill allowing him to affirm was defeated in Parliament. In 1886 Bradlaugh was finally allowed to take the oath, and did so at the risk of prosecution under the Parliamentary Oaths Act. Two years later, in 1888, he secured passage of a new Oaths Act, which enshrined into law the right of affirmation for members of both Houses, as well as extending and clarifying the law as it related to witnesses in civil and criminal trials (the Evidence Amendment Acts of 1869 and 1870 had proved unsatisfactory, though they had given relief to many who would otherwise have been disadvantaged). Bradlaugh spoke in Parliament about the London matchgirls strike of 1888.

Bradlaugh’s funeral was attended by 3,000 mourners, including a then 21-years-old Mohandas Gandhi. He is buried in Brookwood Cemetery. A statue to Bradlaugh is located on a traffic island at Abington Square, Northampton and he is remembered annually on the Sunday closest to his birthday, 26 September. The commemoration starts at 3pm and attendees are invited to speak about Charles Bradlaugh. The commemoration started in 2002 and 2012 was its eleventh year. The statue points west towards the centre of Northampton, the accusing finger periodically missing due to vandalism. Various local landmarks are named after Bradlaugh, including Bradlaugh Fields nature reserves, The Charles Bradlaugh pub, and Charles Bradlaugh Hall at the University of Northampton.

Of interest:

Hypatia

Bradlaugh

Bonner (1858-1935) ‘…

was a British peace activist, author, atheist and freethinker, and the

daughter of Charles Bradlaugh…’

Hypatia

Bradlaugh

Bonner (1858-1935) ‘…

was a British peace activist, author, atheist and freethinker, and the

daughter of Charles Bradlaugh…’

Hypatia was a patient of Charles Drysdale (J. Miriam Benn, The Predicaments of Love, (Pluto Press, 1992). Page 25).

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypatia_Bradlaugh_Bonner She was born Hypatia Bradlaugh, at 3 Hedger’s Terrace, Hackney, London, the second daughter of Charles Bradlaugh, the first openly atheist Member of Parliament and founder of the National Secular Society, and Susannah Lamb Hooper. She was named after Hypatia, the Ancient Greek philosopher, mathematician, astronomer and teacher, who was murdered by a Christian mob.

Bradlaugh Bonner was educated in private schools in London and Paris, and qualified as a science teacher from the University of London, which admitted women to “full privileges” (i.e. degrees) in

- She taught in the Hall of Science for the South Kensington Science and Art Examinations, and also acted as a secretary for her father after 1888.

The Halls of Science were mainly for adult education and self-help, like those offered by Mechanics’ Institutes and religious organisations at the time. The South Kensington Hall of Science was started by Edward Aveling, and other teachers included her sister Alice Bradlaugh (1856–1888) and Annie Wood Besant. The results from the South Kensington Hall of Science were very good, with students exceeding the national average on their examinations in all but one of their offered classes. Bonner was also a lecturer for the National Secular Society and the Rationalist Press Association.

Bonner is most remembered for being the author of her father’s biography, Charles Bradlaugh: His Life and Work. The Spectator considered the two volumes to be more memoirs than a biography: “That it is preposterously long is manifest at once. More than eight hundred closely printed pages are too much for Charles Bradlaugh, viewed in regard to his real importance in the world”, but accepted, “A day will come when they will be found useful”. From 1897 to 1904, she was editor of The Reformer… she was an active contributor to many secularist periodicals including the National Reformer and author of many other books relating to secularism, blasphemy and freethinking. In Penalties upon Opinion she catalogues various trials and cases of blasphemy including the recent revival in blasphemy prosecutions in the first decades of the 20th century.

In the lead up to the First World War most peace societies were Christian associations. In 1910, Bonner became the chairperson of the first secular peace society, the Rationalist Peace Society. The aim of the society was to “protest against ideas and methods which are utterly opposed to reason and the interests of social progress”. In her introduction to Essays towards peace, Hypatia noted that there was a “growing public opinion in favour of arbitration as the alternative to war” and that it was reason that demonstrated “the futility, the brutality, the economic waste, the immorality of war”. The Rationalist Peace Society remained active throughout the war, but fell into decline after peace was concluded.

She married Arthur Bonner in 1885 in Marylebone, London. They had two children, Kenneth (1886-?) and Charles Bradlaugh Bonner (1890-1966). She died at home on 25 August 1935 at 23 Streathbourne Road, Tooting, London, after an abdominal operation for cancer. She was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium on 28 August, and her ashes were buried in her father’s grave at Brookwood.

*Edward Truelove

(1809-1899) Edward

Truelove was also prosecuted for publishing the writings

of Robert Dale

Owen (Edward

Truelove, In the High court of justice. Queen’s bench division,

February 1, 1878. The queen v. Edward Truelove, for publishing …

Robert Dale Owen’s ‘Moral physiology’, and a pamphlet, entitled

‘Individual, family, and national

poverty’, (1878)).

*Edward Truelove

(1809-1899) Edward

Truelove was also prosecuted for publishing the writings

of Robert Dale

Owen (Edward

Truelove, In the High court of justice. Queen’s bench division,

February 1, 1878. The queen v. Edward Truelove, for publishing …

Robert Dale Owen’s ‘Moral physiology’, and a pamphlet, entitled

‘Individual, family, and national

poverty’, (1878)).

From http://philosopedia.org/index.php/Edward_Truelove ‘… An English publisher, Truelove early in life embraced the views of Robert Owen and for years was secretary of the John Street Institution *[an early Owenite socialist group]. He published Voltaire’s Philosophical Dictionary, Paine’s complete works, d’Holbach’s System of Nature, and Taylor’s Syntagma and Diegesis. For a year, he worked at the Owenite utopian community of New Harmony, Indiana. In 1852, Truelove opened his own bookstore in the Strand and later opened another shop in Holborn. In 1858, after he published Tyrannicide by W.E. Adams, Truelove was charged with blasphemy, but the prosecution was withdrawn. In the 1870s, Truelove served four months in prison for the publication of Robert Dale Owen’s Moral Physiology, addressing population and birth control. According to historian Joseph McCabe, “His admirers presented him with £200 after his release*…’